Lava Diva erupts again, rekindling memories of when it set local stages on fire

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on palabra, the digital news site by the National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

By Abraham Márquez

On a July afternoon in 1991, Oscar Guerrero grabbed his skateboard to cut across the busy parking lot of the Pep Boys auto parts store on Spruce Street at the edge of downtown Inglewood. He moved through parked cars and walking traffic, looking over his shoulder to avoid confrontation with anyone, and turned onto a big avenue that would take him to Westchester, one of the many suburban towns hugging Los Angeles.

“I’d take Arbor Vitae Street west all the way,” Oscar said recently, remembering one of his regular treks to the spot where he spent much of his youth. “Once I passed the Shakey’s (pizza joint), I knew I was close,” he added.

After three miles of kick-push-glide, he arrived at a vast parking lot that served patrons of the former Ross discount retailer, a small pizza spot, and Soundsations Records, one of the oldest record stores in Los Angeles. He had saved enough money to buy the new cassette tape by Fugazi, a post-hardcore band from Washington, D.C. It was the band’s second studio album, “Steady Diet Of Nothing.”

“I’m spending hours there looking through cassettes, and I would pick three or four, even though I know I can only afford one,” Oscar said.

For teenagers like Oscar who craved music and culture beyond the Tower Records’ mainstream of the day, Soundsations Records was the place to find the latest tapes and records on the cutting edges of the rock, soul, and emerging hip-hop universes. Latino and Chicano artists like Cypress Hill, Rage Against the Machine, and Big Pun emerged and made significant contributions to the music scene, resonating with a generation breaking from the traditional rock of the 80s. And for young Latinos in Southern California, they became the bedrock of all the new music of the day, from Red Hot Chili Peppers to Morrissey, Jane’s Addiction, and Lava Diva. The last one, rose to the top of the playlist for Oscar and his friends.

They’d also leave with the latest free editions of LA Weekly, the alt-weekly publication, filled with reporting from the cultural front lines of the region’s bustling entertainment industry. “I would grab the paper and look for shows to go to with my friends,” Oscar said.

Afternoons at Soundsations Records would last hours, often leading Oscar to hurriedly roll back to Inglewood before it got too late.

It was worth it, Oscar said. It was the best way to ride the waves of the newest music. And it also helped them keep track of Lava Diva.

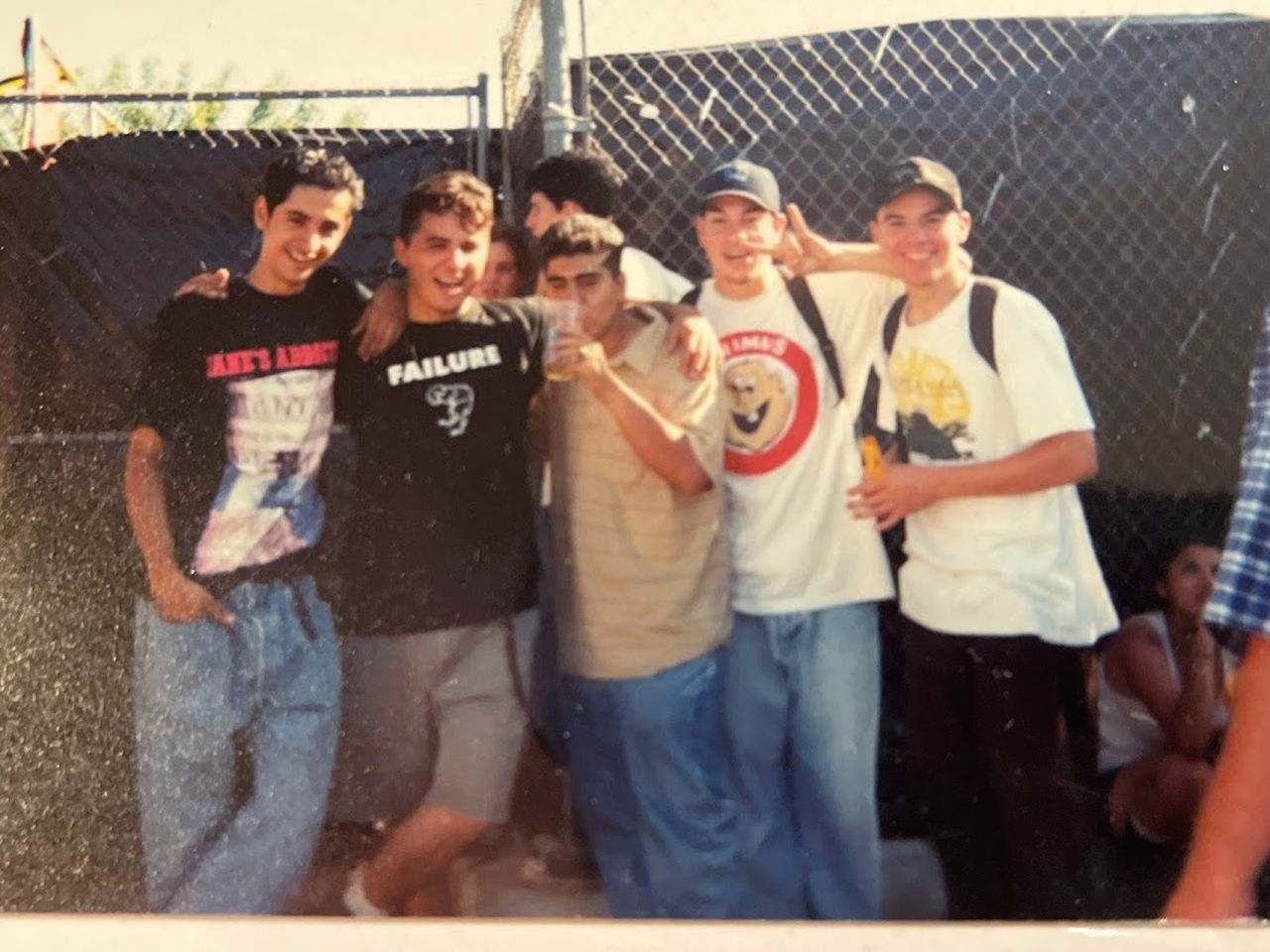

From left to right: Jesse Márquez, Rafa Gradilla, Miguel Martinez, Oscar Guerrero, and Gerardo Gradilla at the second Lollapalooza in 1992 at the former Irvine Amphitheater. Photo courtesy Jesse Márquez

“I was one of the first ones to drive in high school,” said Jesse Márquez, one of Oscar’s childhood friends and my oldest brother who introduced me to the band. “I’d take my dad’s 1975 Ford LTD, pick everyone up, and go to a show,” he added. Oscar and Jesse first saw the band play in someone’s loft in Venice, near the beach off Main Street. Almost everyone left the show with the band’s well-known red demo tapes. At Inglewood High, Oscar and Jesse’s tapes circulated among friends. Each time the cassette was passed on, Lava Diva gained a new fan in one of the nation’s most challenging places to “make it” as a band. Moreover, the underground legion of fans in the early 1990s would boost Lava Diva for years to come.

Lava Diva features Dawn Lunsford with vocals and guitar, Greg Berella on percussion and drums, and Johnny Whitman on bass. From 1992 to 1998, the trio played before a dedicated fan base in all of Los Angeles’ iconic live music venues. They were on stage before and after some of the time’s iconic live acts, like Girl Jesus and Rage Against the Machine.

Then, around 1999, Lava Diva went dark. The trio focused on a new lifestyle around family and work. The grind of live shows and studio time was in the rearview mirror.

The band seemed lost to a history of independent rock music – an analog time powered by notices in alternative periodicals and word of mouth – that seemed to end with the rise of the Internet and social media.

But then came the announcement in December 2021 that the original trio would reunite for a set of live shows.

It reminded fans like Oscar of the unknown bands from the generation before social media, when talented musicians would talk to each other and then maybe come together to rock a stage or a backyard. Some hit the big time. Others won cadres of followers before moving on to lives, family, and workday careers.

Lava Diva, however, is a reminder that, if the stars align, stellar musicians might regroup for a nostalgic tour or an anniversary show – guaranteed to bring out the fans, most now within sight of middle age.

Music Under Curfew

On April 29, 1992, on the seventh day of deliberations, a jury acquitted four L.A. police officers of criminal charges stemming from the brutal beating of Rodney King. For the next six days, people in parts of Los Angeles took to the streets to express their anger at the system that did not appear to see what they’d seen, played over and over again on television. Crowds shut down major intersections in the historic South Central neighborhood as protests spread throughout Southern California. On day two of the protests, then-Los Angeles City Mayor Tom Bradley called for a dusk-to-dawn curfew.

Some 30 miles north of the social fire, and amid orders to stay off the streets, three friends managed to come together to map out a musical journey. They would become the frets and strings of a music community and an iconic part of the Los Angeles rock scene.

“We both worked for the (public) school system,” Johnny Whitman, the bassist, told palabra in an interview. “I worked for Cal State Northridge, and Dawn worked for the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), so we couldn’t go to work or do much under curfew,” she added. Nevertheless, and to Johnny’s amazement, Dawn asked if she wanted to get together to play music during the curfew. What seemed like a casual jam-out session – killing time with a longtime friend – became the beginning of something special. “I didn’t play music at all. I just liked music and going to shows,” added Johnny, who was an avid concertgoer at the time. She was also an emerging musical talent, taking lessons from Rage Against the Machine guitarist Tom Morello, who she’d met at a show in 1990. (Johnny and a friend had booked Morello’s previous band, Lock Up, for a campus gig at Cal State Northridge – only to find out that the band had broken up and could not perform.)

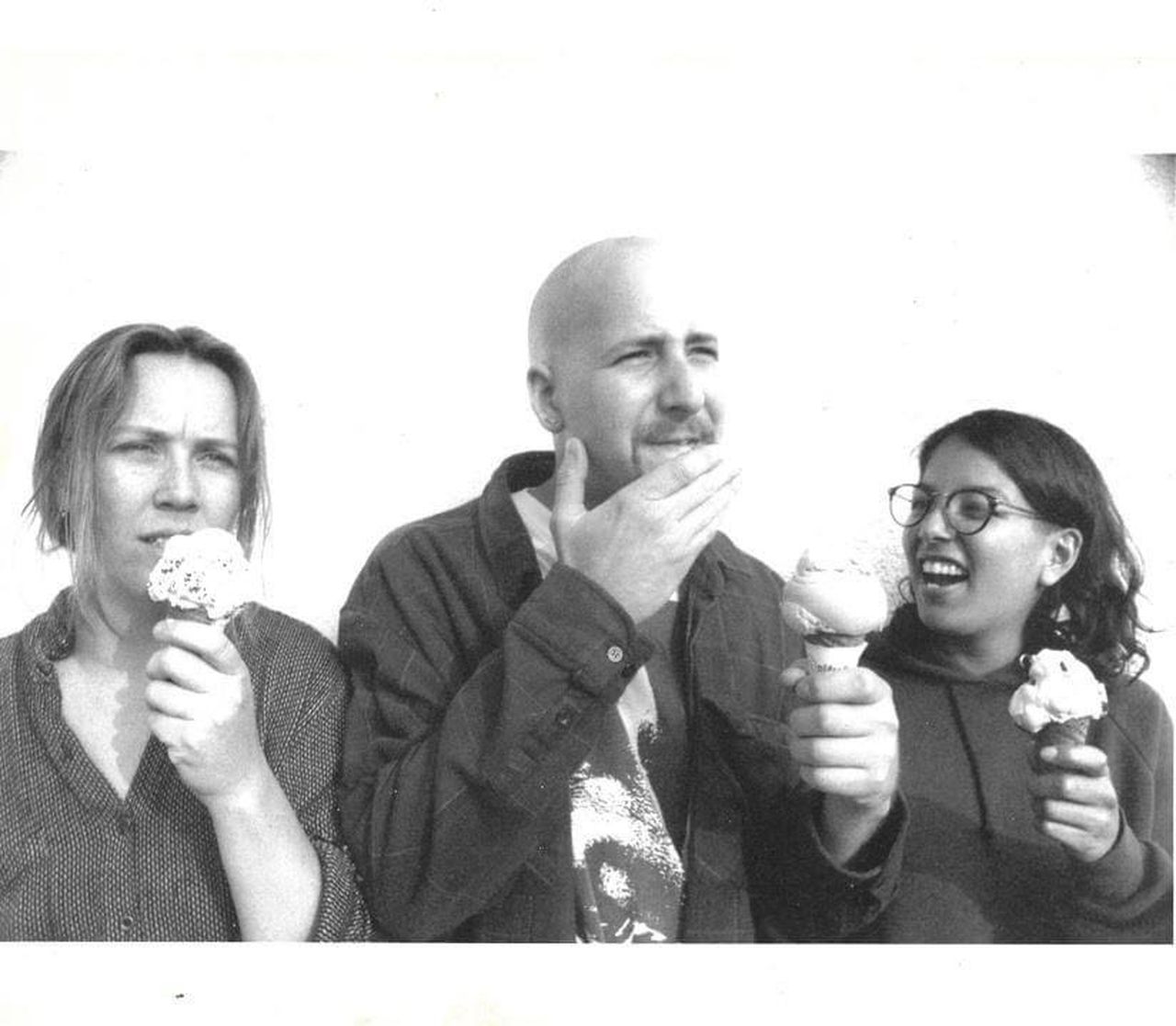

Lava Diva photoshoot in Van Nuys, CA, in 1995. This photo will later be used for their first studio album. Photo courtesy of Lava Diva

With Southern California in the grip of social tension, its music landscape changed tracks. By then, alternative rock had been coined to accommodate bands that didn’t fit into the radio-play mainstream category. Far to the north, near the Cascade Mountains of Washington State, grunge music was in its bloom.

Media and the masses embraced the two genres. And in Los Angeles, the music crossed cultural lines. New fans in the Asian, African, Latino, and Chicano communities attended live shows. Alternative and grunge acts went mainstream as labels and clubs saw the market potential of sounds attracting diverse audiences.

This new generation of musicians was comfortable playing in small venues filled with fans who learned about their gigs by word of mouth. “In the 90s, promoting a show was personal,” said Chris Long, also known as “Hot Rod,” who promoted shows for the Whisky a Go Go, Coconut Teaszer, Club Lingerie, and Raji’s – a little club snuggled in the darkest corner of Hollywood where Nirvana played in 1990. “First, I had to find someone who owned a computer and make sure they knew how to design fliers,” he added. He would then walk around town, talking to people and inviting them to the show, encouraging them to bring friends. “This is how I built a following before social media.”

When Dawn invited Johnny to play, she was looking for something different. Her previous musical journey, a pop-folk-style band called Familiar Spirit, had broken up. At that time, she only worked with an acoustic guitar. Later, Dawn told Johnny that she wanted to go electric. Morello took on both as students.

While they were learning to play together, the Los Angeles fire department extinguished the last embers of the post-verdict fires. Buoyed by a community reawakening, the childhood friends hit a rhythm and wrote some songs. Then came the search for a drummer.

Dawn invited Greg Berella to sit in. “I had played percussion for Familiar Spirit, but also knew how to play the drums,” Greg said. He became Lava Diva’s first drummer, but was not yet an official band member. “For the longest time, he did not want to commit,” Dawn remembered. “So in the early days, we kept announcing that we are looking for a drummer at shows” – an announcement repeated for over a decade.

Even now, Dawn can’t resist tossing a barb his way. “Are you staying? Because you are still here,” Dawn said, sparking laughter at the table in Johnny’s dining room where we all gathered to talk and snack on grapes, cheese, and crackers.

As the city’s curfew was lifted, skeleton-like structures left from the fires, streets coated with ash, cops back on patrol, and LAPD helicopters roaring over the city, the Lava Diva band was born.

A unique sound and look

Part of the Lava Diva’s sound and look was Greg’s unorthodox percussion and drum setup, to which he added chimes and swapped a congo for the bass drum. The unique array, and sound, added to Dawn’s soaring voice and Johnny’s agile bass playing. It was only a matter of time before they rocked the stage with songs they created while under curfew in 1992.

Lava Diva, a band led by two women – one in the LGBTQ community – was entering an industry dominated by men and misogyny. But by 1992, the landscape was evolving. “We felt welcomed and not excluded,” Johnny said. “By the time we started playing, there were a lot of groups led by or had women in them,” Dawn added. They joined a list of incredible female-led bands like Concrete Blonde, 7-Year Bitch, Girl Jesus, and Down Girl.

In the center of metropolitan Los Angeles, the West Hollywood community features a robust cultural center and a small club, The Whisky a Go Go, an iconic rock landmark on the Sunset Strip. It was a launchpad for acts like The Doors, Frank Zappa, Van Halen, Soundgarden, and many more. That buzz and reputation alone brought people into the venue on any night in the 80s and early 90s. Everyone wanted to catch an early glimpse of that “next big band.”

Whisky a Go Go was Lava Diva’s first commercial venue. “Hot Rod gave us a midnight slot,” said Dawn. They assumed the venue would be lightly attended and could serve as an easy first show. But things didn’t go as planned. “I fucking hated it!” said Johnny, placing her two hands firmly on the dining table. “Keep in mind, Greg and Dawn have been doing this together for almost a decade. This was my first time performing live,” and in the audience were friends and members of the many local bands she had supported as a fan.

“You were probably nervous because you knew everyone there,” Greg told Johnny as he bit into another grape.

After their first show, Johnny told the band she did not want to keep playing if things didn’t improve on her end. “The second show was just as bad, if not worse,” said Johnny, while she glanced at each member reminiscing of the early struggles. “The third show was fun, but I don’t remember where it was. I just remember having a lot of fun,” she added, remembering that Dawn was a big help in her getting comfortable on stage. The sound coalesced as the band started to work out the kinks of a live set, and so did the buzz about Lava Diva.

Mastering the live show

Over the last three decades, there’s been a revolution in how bands are promoted and their music distributed.

But back in the early 1990s, “it cost a lot of money and time to promote your show and record your music,” Greg said. When a live show was lined up, the band organized an assembly line at the Kinkos copy machines, “one person was responsible for stamping, one for cutting the fliers, one for placing the labels on the postcard,” Dawn said. The band paid around $350 to send out postcards. And, for upwards of $50, they’d get an all-important ad in the LA Weekly.

On December 14, 1992, they were once again invited to play the Whisky a Go Go. This time they would be lined up with bands they were already friends with, including Stanford Prison Experiment, Into Another, Greta, and Rage Against the Machine. The show was a success.

From 1992 to 1998, they performed across the city in almost every notable venue. For fans, the Lava Diva sound became a raw timestamp for the 90s. It was a traditional band with guts and moving lyrics that got the attention of local media. The group was featured in Seattle Weekly, Female FYI Magazine, Los Angeles Reader Magazine, The Mailing List, The Silverlake Local, and many more.

A highlight, Dawn said, was being invited to play the ‘Rock Against Rape’ benefit show. They opened up for Concrete Blonde, Courtney Love, and Kurt Cobain. It was hosted at the intimate Club Lingerie, which had been “the hottest Hollywood rock venue this side of the Whisky” and a bit of a performance home for bands such as Red Hot Chili Peppers, Weezer, Korn, and Sublime. (Cobain and Love surprised the audience with their collaboration. “This is the first and last time you’ll ever see this happen,” said Love. She was not lying. Musically, the two figureheads of the 1990s only shared the stage once. The only other time was at their wedding.)

The Lava Diva buzz also attracted attention from some record labels, but the deals fell short of the band’s expectations. “We didn’t want to sign something that would jeopardize our livelihoods,” said Dawn.

Yet even without a recording deal, the band kept its strong fan base with live shows.

After six years of playing across L.A., Lava Diva self-released its first album in 1998, featuring twelve songs, including Jesse’s favorite, “Backyard BBQ.” Two years later, they released a twelve-track acoustic album, “Creeks and Dogs.”

Lava Diva had hit its stride with the recordings, but by 2000, the band stopped the string of live shows. The run had ended.

“We didn’t break up, but life happened,” Dawn said.

Johnny and Greg became partners and parents. Dawn married her partner Cara Lunsford and started a family. The bandmates remained friends, but they stopped playing together. Dawn launched a solo career and toured the region. Greg joined another trio, The Baby Goats.

It was never The End

Decades removed from the last live gig, the three are raising families. They were friends first, and today they remember how tough it was to turn their art into a living. It took the right mix, the ex-bandmates said. It is not easy finding people to start a band with, let alone stick together through decades of life’s obstacles.

And, yes, the passion for their music remains. Recently, a friend casually approached them about returning to the stage. “We looked at each other and said sure, why not,” Dawn said.

Rehearsals were scheduled, now set around their family lives.

“It is more difficult now to find time for rehearsals than thirty years ago,” Dawn added.

They’ve since navigated the COVID pandemic, full-time jobs, and family responsibilities.

But it’s been technological advances that have enabled the Lava Diva reunion.

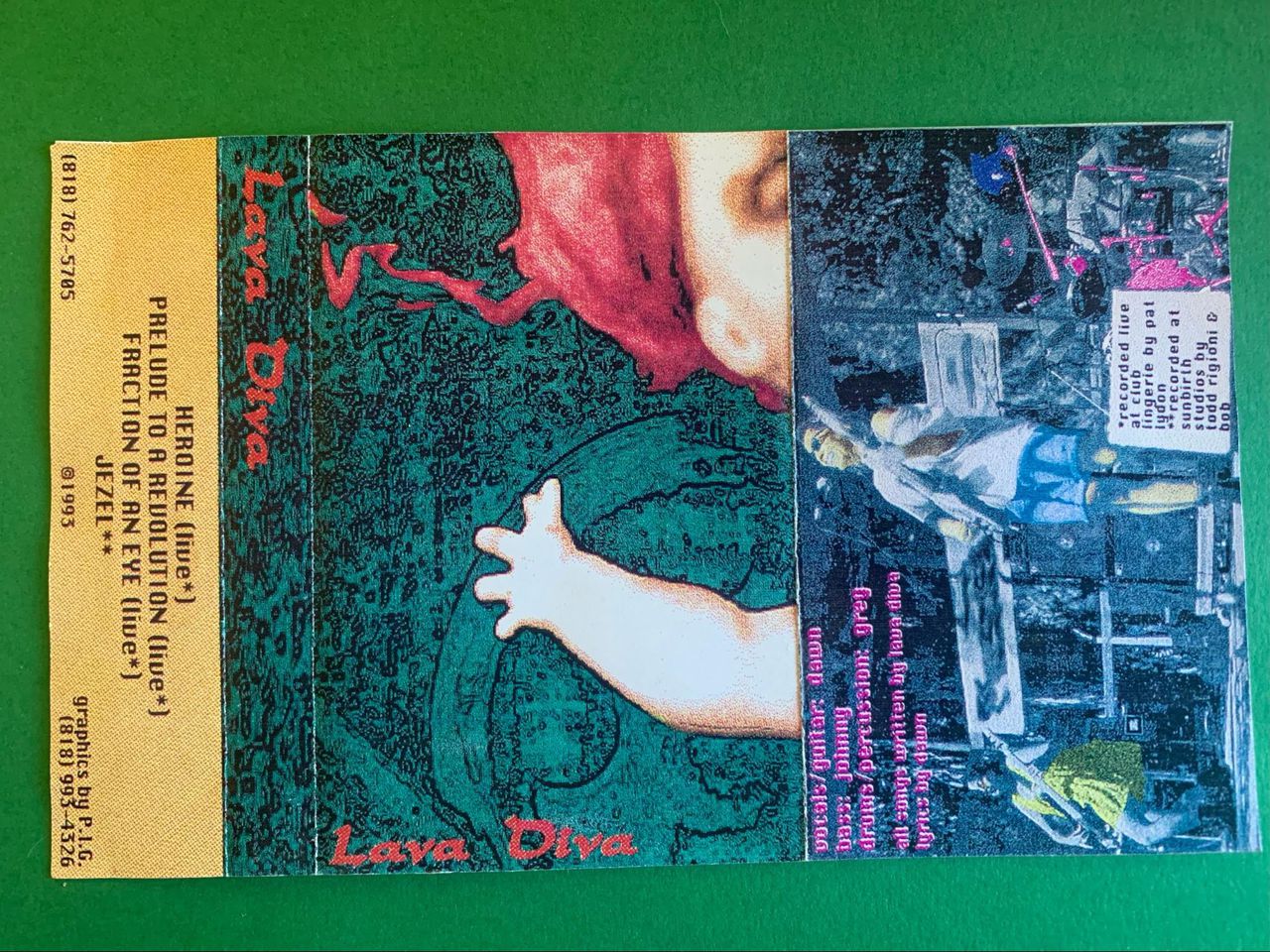

J Card for Lava Diva’s live demo tape in 1993. Tracks including “Heroine,” “Prelude to a Revolution,” and “Fraction of an Eye,” were recorded live at Club Lingerie by Pat Lydon. The track “Jezel” was recorded live at Sunbirth Studios.

“We recorded our first album on two-inch tape and created J-Cards,” Johnny said. “Today, you can record a whole album on your phone.” And social media, which in the early 90s meant power-pole posters and shout-outs at parties, today means covering a whole region with well-crafted Tweets or short Instagram videos.

“Our drive has not changed. We want to keep playing for the love of playing live and making music,” Dawn said. “I like where we are going, and let’s see where it takes us.”

On Jan. 15, 2022 – 30 years after their first stage show – Lava Diva played the renowned Cobalt Cafe in North Hollywood. The original Cobalt was a pillar for the alternative music scene in the San Fernando Valley in the 90s, where bands like Incubus, Hoobastank, and Linkin Park performed. Since then, they’ve toured the L.A. area’s live venues again and even returned to the Whisky a Go Go. And like old times, a legion of loyal fans has followed.

“It is amazing that thirty years later, they still got it,” Oscar said. “Their live set still kicks ass.”

__

Abraham Márquez is a National Association of Hispanic Journalists member and a 2021 USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism Fellow. He is also a Los Angeles correspondent for the Bolivia-based Kawsachun News outlet.

Ricardo Sandoval-Palos is an award-winning investigative journalist and editor whose career has spanned four decades. In May, Ricardo was named Public Editor – ombudsman – for PBS, the nation’s leading public media outlet.