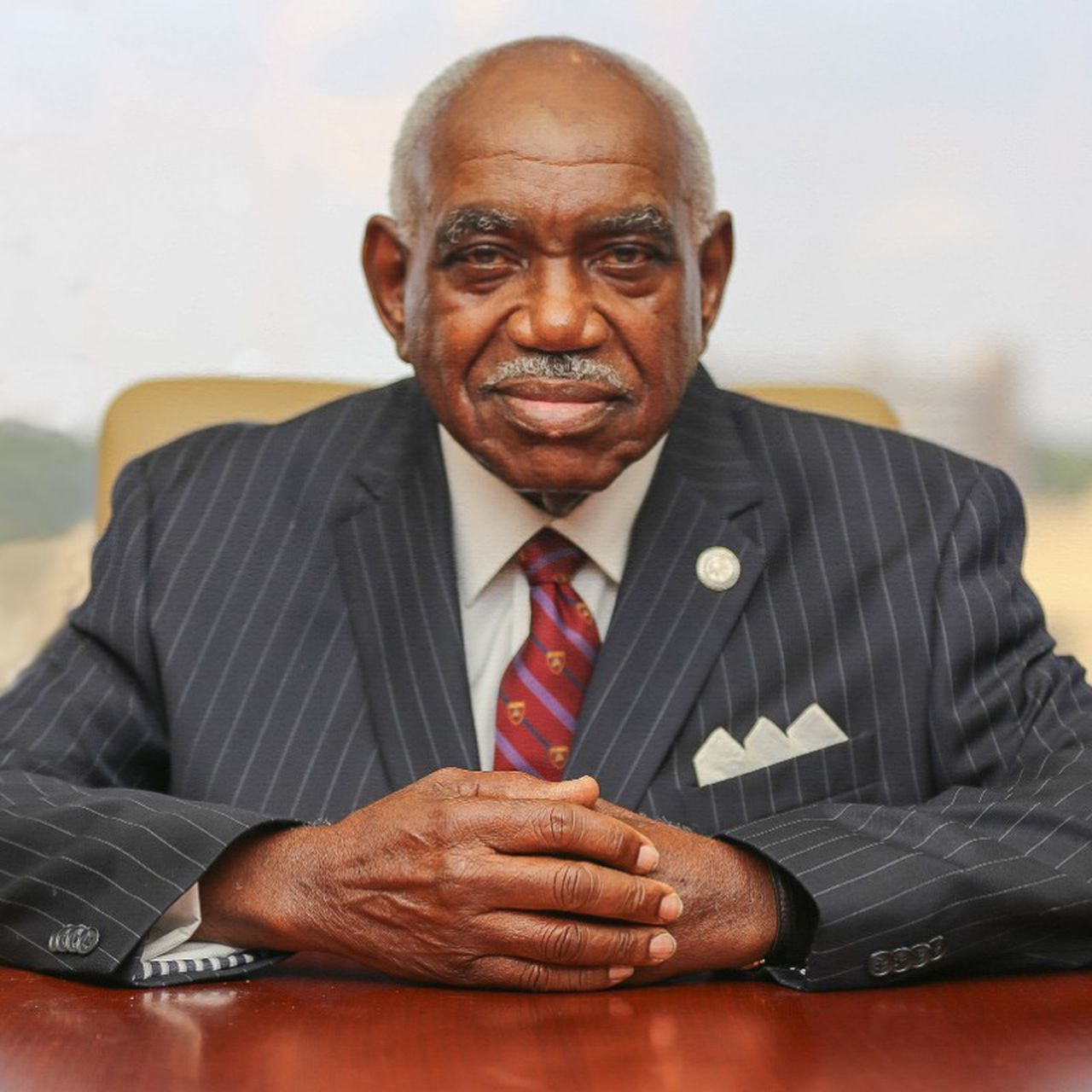

Guest opinion from retired federal judge U.W. Clemon: Time to expand the Supreme Court

This is a guest opinion column

Like April 13, 1896 (the date of the Plessy v Ferguson “separate but equal” case), June 29, 2023, is a date that will live in constitutional infamy. For on that disdainful date, a divided United States Supreme Court abolished affirmative action in the nation’s colleges and universities in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard College and the University of North Carolina (which I choose to call “the unfair cases”).

As a longstanding beneficiary of affirmative action, I am outraged by the unfair cases and hereby make the outcry. It’s high time to expand the nine-member Supreme Court (set by Congress in 1869) to a more just and representative thirteen members in 2023 in the twenty-first century.

Just eighty years ago, I was born in a racially segregated Jefferson County, Alabama – the legality of which had been sanctioned by the Supreme Court in the infamous “separate but equal” case. My education transpired in all-black, segregated and unequal schools – beginning in a broken-down wooden elementary school building with outdoor toilets and no playground just three blocks away from a new brick elementary school with indoor plumbing and a playground for whites only. Our textbooks were passed on to us after they had been used and discarded by students at the white school. At age 13, after witnessing police terrorism, I decided to become a civil rights lawyer. The doors of the University of Alabama were closed to me when I graduated as valedictorian of my high school class in 1961.

So, I attended the unaccredited black private Miles College in Birmingham. There, I was a student leader who confronted Eugene “Bull” Connor. A year later, I actively participated in Dr. Martin Luther King’s 1963 Birmingham Demonstrations, desegregating the Birmingham Public Library. When I graduated in 1965 as student body president and valedictorian of my class, the University of Alabama Law School remained closed to blacks. But the State of Alabama had a program which would pay me as a black student the difference between the tuition and lodging at the University of Alabama Law School and any non-segregated out-of-state law school of my choice. Because of the association of some of its professors (Walter P. Gellhorn and Jack B. Weinstein) and graduates (Jack Greenberg, Constance Baker Motley, and Robert Carter) with the civil rights movement, I chose the Ivy League Columbia Law School in the City of New York.

That’s where affirmative action kicked in. The lack of a degree from an accredited college would ordinarily have been a bar to my admission to Columbia, where well over half of the 300 entering class members held degrees from Ivy League colleges. But my college president had a friend at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (“LDF”), who in turn had an association with LDF board member and Columbia Law Professor Walter P. Gellhorn. I applied to Columbia; and under its new affirmative action program, I (along with eight other black students, including James Meredith of Ole Miss fame) was admitted to the entering class of 1965.

The first semester of my first year at Columbia Law School was a significant cultural and educational challenge for me. But I worked hard, kept my eyes on the prize, and by the end of the second semester, I felt quite comfortable at Columbia. When I graduated in 1968, turning down my professors’ offers to place me in a Wall Street law firm, I immediately returned to Alabama to practice civil rights law, subsidized by LDF.

I was one of the lawyers who argued the case, Singleton v. Jackson Separate Municipal School District, which desegregated public schools throughout the South in 1970. I was one of the lawyers handling the United States and McKinstry v. United States Steel Corporation, which broke down the barriers of segregation in the steel industry nationwide. I sued Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant in 1969 to desegregate the all-white University of Alabama’s football team. I was one of the first two blacks elected to the Alabama State Senate, where I chaired the Rules and Judiciary Committees and did battle with Governor George Wallace.

Twelve years out of law school, President Jimmy Carter appointed me, and the United States Senate unanimously confirmed me as Alabama’s first black federal judge – a position in which I proudly served for nearly thirty years. I was the first of my Columbia Law School class to be appointed to a federal judgeship.

That is what affirmative action has done for me.

I have taught, lectured, and written law review articles for the University of Alabama Law School. I have received the highest awards of the Alabama Bar Association, the National Bar Association, and the American Association for Justice. I have also received the John Pickering Award of the American Bar Association and the Thurgood Marshall Lifetime Achievement Award of the NAACP LDF. My post-judicial retirement case terminating a splinter school system, as reported by Nikole Hannah-Jones, was the cover story for the New York Times Magazine in September 2017.

My life is proof that affirmative action works!

But putting aside what affirmative action has done for me personally, I deeply appreciate that racial discrimination is yet endemic in the fabric of American society. As a federal judge for over three decades, I frequently presided over cases in which racial discrimination was proven. As a civil rights practitioner over the last dozen years, I continue to see the ugly head of racism in high and low places throughout this nation. The State of Alabama, under federal court order, only dismantled its racially segregated college and university system less than twenty years ago.

Not unlike my personal predicament nearly three-quarters of a century ago, today, nearly half of all black and Latino students attend racially and ethnically segregated, inferior schools in our nation’s urban areas. Right now, there is no light at the end of the tunnel for them because sixteen years ago, the Roberts Supreme Court held in the Seattle school case that students in racially and ethnically segregated schools are doomed to their fate. The immutable teaching of Brown is that “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” Thus, today’s graduates of racially and ethnically segregated and unequal public schools likely will likely not be admitted to the better colleges and universities. That is, in the absence of affirmative action.

The soon-to-be legendary dissents of Justices Sotomayor and Jackson in the Unfair Case well make the point. Particularly impressive was the dissent of Justice Jackson, whose admission to Harvard Law School was not based on affirmative action but rather on her stellar undergraduate record. Regrettably, Justice Clarence Thomas (the second black to serve on the Supreme Court), who now has amnesia regarding 1971 admission to Yale Law School, chose to help burn the bridge of affirmative action after he had crossed over to reach his present position.

Nevertheless, it is crystal clear to me that the time is right to expand the size of the Supreme Court. The power of the nation’s highest court – since it lacks either an army or a treasury to enforce its orders – rests on the confidence of the people that it will do the right thing. Not only has that confidence been profoundly shaken by the recent ethical transgressions of several of its members; it has equally been challenged by the increasing trend of the court to bring an end to established and cherished constitutional rights. Like, for example, the right of a woman to have a voice in the use of her body; or the right of the LBGTQ community not to be discriminated against because of its sexual orientation. In sum, the present Supreme Court has been tone-deaf to the crucial needs of the 21st century.

There is a viable alternative. The Constitution delegates to the Congress of the United States the power to determine the number of justices of the Supreme Court. What’s the use of the possession of power if it is not used when needed?

We need Congress to exercise its power now!

In 1869, when the number of judicial circuits was increased from seven to nine, Congress expanded the size of the Supreme Court from seven to nine members. The country has grown mighty since that time: in population, problems, institutions, and complexity. The number of law schools has grown in this country from a handful in 1869 to nearly 200 accredited law schools in 2023.

A nine-member Supreme Court (eight of them with law degrees from either Harvard or Yale) with lifetime tenure, is simply too small to be the final voice of the nation on vital constitutional issues in 2023. Congress needs to expand the size of the Supreme Court to reflect the thirteen judicial circuits in the nation and its explosive changes since 1869.

The expansion of the nation’s highest court is a cause to which I, a proud affirmative action beneficiary, am committed for the rest of my life.

The Honorable U.W. Clemon is a civil rights attorney and serves as ‘Of Counsel’ for Mehri & Skalet, PLLC. He was the first Black federal judge in Alabama, serving as the chief judge of the Northern District of Alabama from 1999-2006.