âPantherâ podcast connects historic Lowndes County voting movement with party that scared America

This is an opinion column.

If there’s something in America more powerful than the vote, the Founding Fathers—imperfect, though they were—kept it (and that powerful vote) to themselves. Just as they kept it from women and the Black people most of them enslaved.

That’s why the Constitution needed the 15th and 19th Amendments.

Why Blacks in the South were forced to count jellybeans in a jar, take unpassable quizzes, or risk losing their lives simply to register to vote.

Why hundreds of people tread 51 miles along Alabama’s Highway 80 from Selma to Montgomery. Or were beaten by state troopers while trying to do so.

Why Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1964.

Why soon thereafter the Black folks of Lowndes County—a majority-Black county just about midway along that historic walk—tested the new federal law by doing something insanely radical: Forming their own political party, a Black political party.

Why a young, skinny activist from New York came south to Lowndes and learned at the feet of those radical Black people, gaining the organizing savvy and inspiration to launch a movement. A movement that still resonates with many today.

Had Stokely Carmichael not ventured to Lowndes, he might never have seen the Black panther, the menacing mascot of that Black peoples’ party—the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. A mascot meant to intimidate the bejesus out of the Republicans’ donkey and the Democrats’ chicken. Yeah, chicken.

A mascot that birthed a national movement. Two movements really—one in Lowndes County more than half a decade ago, another on its heels that reverberated from the west coast to across the nation.

Today, we’re releasing the first two episodes of a new six-part podcast series: Panther-Blue print for Black Power. It chronicles how the Black citizens of that county, nestled in the state’s famed Black Belt, overcame decades of being denied the right to vote with a strategy of organization and empowerment so effective it ultimately led to the election of Black public officials in the county for the first time.

It unleashed power.

It also lit a fire under Carmichael, who unleashed it during a speech in Mississippi: We want … Black Power!

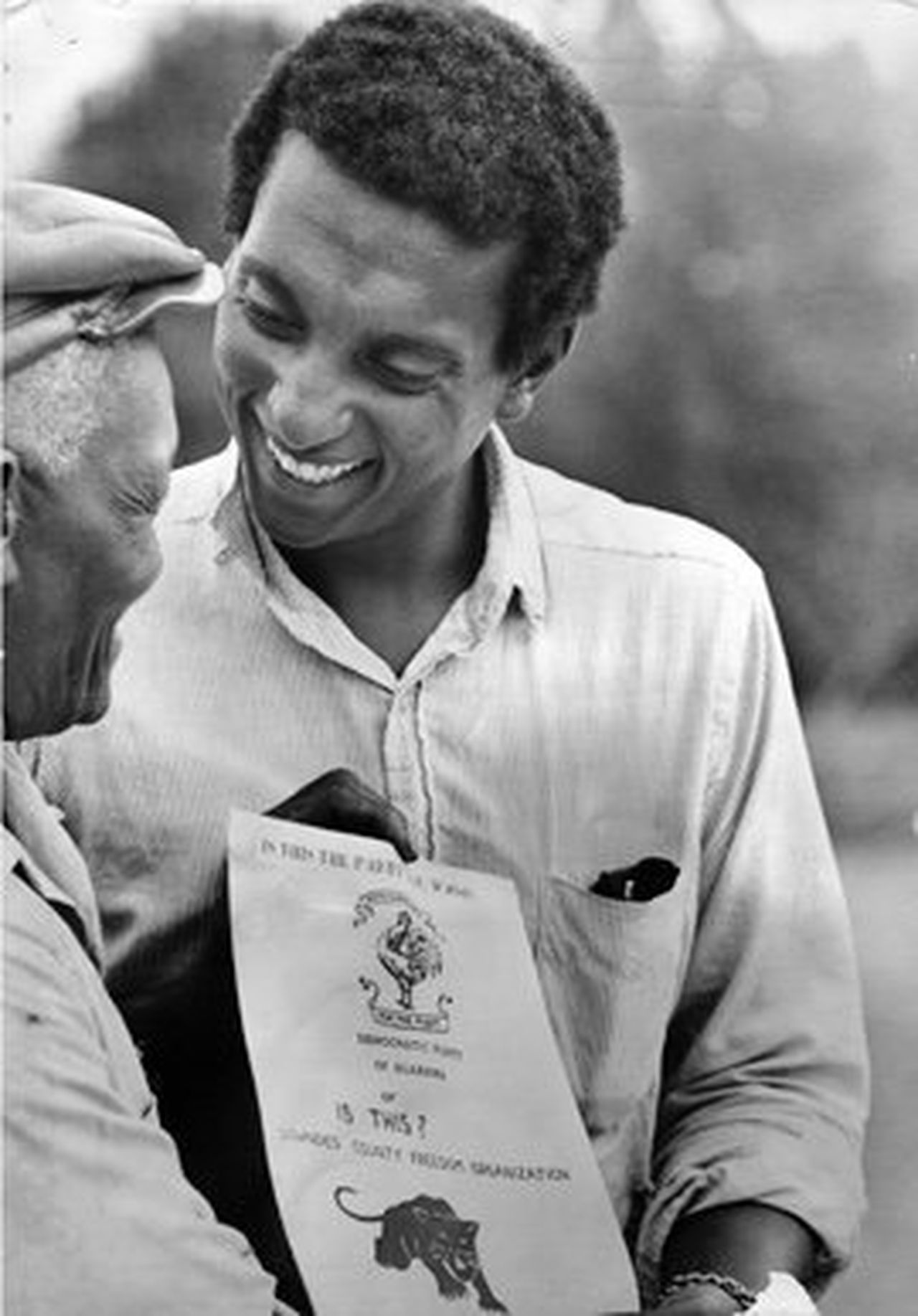

Stokely Carmichael, a SNCC activist. holding a Lowndes County Freedom Organization pamphlet. The logo used by the organization would later be adopted by the Black Panther Party for Self Defense.

That flame touched a group of young men who founded the Black Panther Party, who expanded the strategies and passions of the South to create a self-sufficient movement to educate, elevate, and empower Black communities—and scare the bejesus out of America.

Panther reconnects that bridge with tales of history—history in my lifetime—that you don’t likely know. Because you weren’t supposed to know, as my co-host Eunice Elliott and I share in the podcast.

Because you weren’t supposed to be educated, elevated, and empowered by their truth—just as some still believe our children should not be taught.

Panther features voices that cannot be ignored. Voices from that struggle. Voices of people who faced bullets from angry whites, had their homes stripped from them by angry whites and were told by the white sheriff that he’d nothing to protect them if they tried to meet on the lawn outside the county courthouse, which they were legally allowed—no, required—to do as part of forming their own party.

People like Regina Moorer, Pastor Aaron McCall, Pattie Mae McDonald, Charles Mays Hillard, Viola Bradford, Joanne Mants, Catherine Coleman Flowers, Mary Mays Jackson, Ed Moore King, and Lillian McGill. (King and McGill have passed on since we captured their memories two years ago.)

People who didn’t much worry about none of that (or children whose parents didn’t much worry)—because they could protect themselves. And would.

Because that power, the voting power that had too long eluded them was rightfully theirs, and they were going to snatch it one meeting, one ballot, one vote at a time—with their own party (because back then both the Democrats and the Republicans were racist).

And their own mascot.

The origin of the panther mascot is muddied by history’s haze, but it was clearly and emphatically stamped on the LCFO’s flyers touting its candidates and outlining the specifics about each office.

The LCFO fielded seven candidates for that 1966 election. None of them won (whites paid, and/or threatened some Black residents to vote for their candidates or risk losing their homes, or worse). Five years later, though, one LFCO candidate, John Hullett, was elected as the county’s first Black sheriff.

Today our national leaders are sitting on their hands, stalling even consideration of the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. The late Congressman and ardent activist committed his life to equality, freedom, and access to the ballot—that powerful ballot.

The bill named for him would restrengthen that ‘64 VRA, which was gutted in 2013 by our friends on the U.S. Supreme Court. In Shelby County v Holder, it invalidated a key provision of the law that forbade states with a history of voter discrimination (you don’t need to be a CRT scholar to guess which ones) from changing voting laws without clearance by federal officials.

By a grownup in the room.

Without adult supervision state legislatures throughout the South (and even beyond—legislatures dominated by Republicans—are doing everything but reviving jellybeans jars to deter, dissuade, or detour voters who may not look or think like them.

Which is why we still need the Lowndes County blueprint. Still learn from it. Still wield it.

Powerfully.

Subscribe to Panther: Blueprint for Black Power on Reckon Radio on Apple, Spotify, Google, Stitcher, and anywhere else podcasts are found.