Johnson: 51 years ago today, SCOTUS ruled the death penalty unconstitutional – really

This is an opinion column.

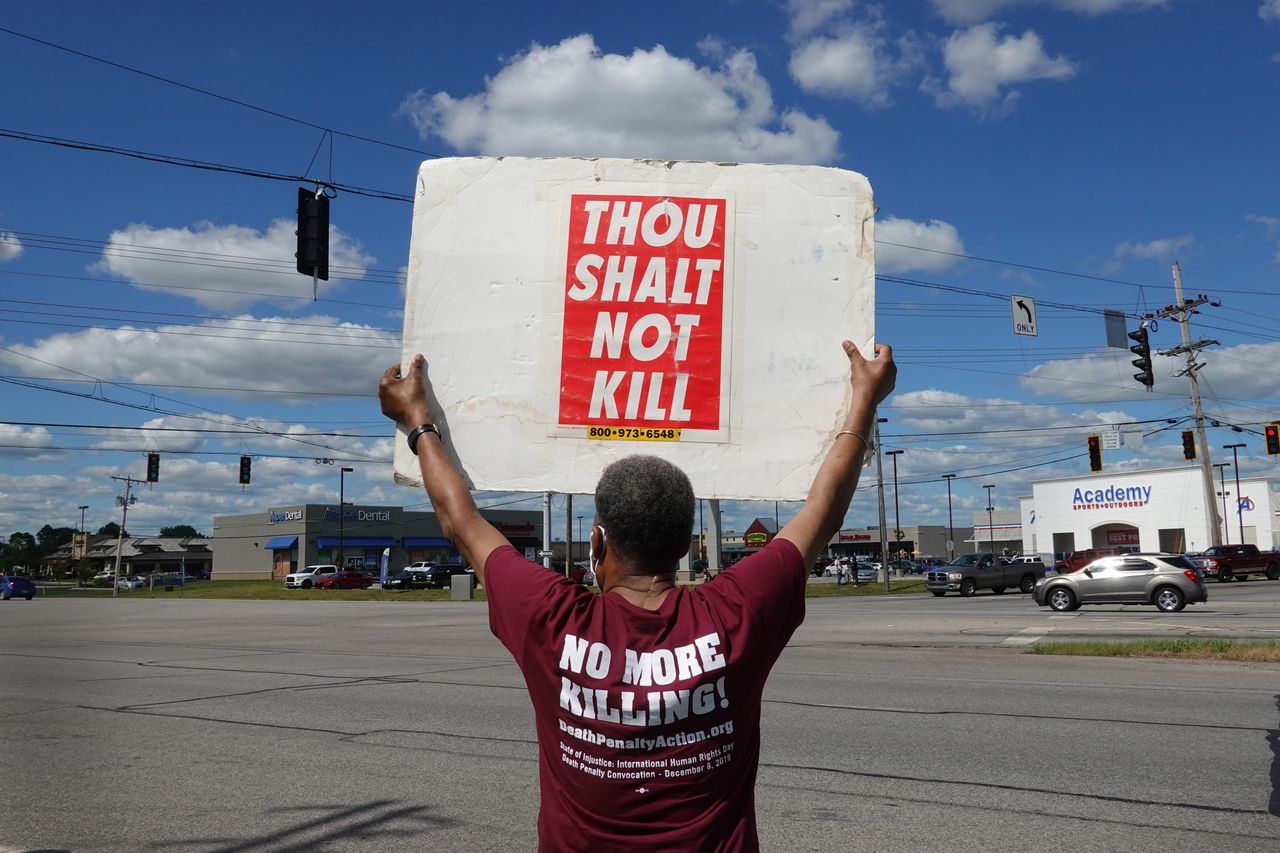

We’re chompin’ at the bit to kill somebody.

Ever since Gov. Kay Ivey’s three-month moratorium on executions ended in February (a necessary hiatus since we kept bumbling and botching lethal ejections), Attorney General Steve Marshall’s office has been eager to kill somebody.

James Barber, specifically, is in Marshall’s crosshairs.

Convicted in Madison County of a 2001 murder, Barber, 64, is slated to be killed at some point between midnight on Thursday, July 20, and 6 a.m. on Friday, July 21.

I’ve long shared my opposition to the death penalty and the reasons for my stance. I wrote this column in 2020 after we killed Nathanial Woods, and this one in 2022 after we killed Joe Nathan James, Jr. over the objection of the victim’s daughters, who said they’d forgiven him.

Jesus forgives—not Alabama.

Unless you’re of a certain age with a Venus fly trap memory, you may not remember that capital punishment was once unconstitutional.

In 1968, William Henry Furman of Savannah, Georgia, was convicted of murdering homeowner William Micke during a burglary attempt and sentenced to death. Furman, a Black man, told police he’d fired his gun blindly behind him while trying to flee Micke’s grasp. He was found to be “emotionally disturbed and mentally impaired” yet was convicted after only one day of testimony. Micke was white.

Furman’s appeal reached the U.S. Supreme Court (along with two similar appeals). His attorneys argued the death penalty was not levied fairly, and that a disproportionate number of those sentenced to death were Black, thus making the penalty in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.”

On this day, June 29, 1972, the nation’s highest court agreed. In a 5-4 decision in Furman v. Georgia, SCOTUS ruled the death penalty unconstitutional. The primary reasoning for those in the majority: The death penalty, as it was being applied by states, disproportionately harmed minorities and the poor.

“These death sentences are cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual,” wrote Justice Potter Stewart. “For, of all the people convicted of rapes and murders in 1967 and 1968, many just as reprehensible as these, the petitioners are among a capriciously selected random handful upon whom the sentence of death has in fact been imposed.”

I was still in high school then and had long forgotten that the SCOTUS had doused the death penalty until I came across the anniversary while doing research for my newsletter, The Barbershop. (Shameless plug: subscribe here or above.)

Alas, the ban lasted only four years.

In that time, 37 states crafted death penalty laws designed to peck away at the ruling. In 1976, they succeed. In Gregg v. Georgia, the court overwhelmingly ruled (7-2) that sufficient progress had been made (ahem) to make capital punishment constitutional again.

In January 1977, Gary Gilmore of Utah, found guilty of murder after killing two men in different robberies, became the first American to be put to death after the resurrection of capital punishment. At 36, he was executed by firing squad. Gilmore was white.

Decades later, Justice Paul Stevens was one of three former justices on that 1976 Supreme Court who expressed regret over their decision.

“I thought at the time,” he told National Public Radio in 2010, “that if the universe of defendants eligible for the death penalty is sufficiently narrow so that you can be confident that the defendant really merits that severe punishment, that the death penalty was appropriate…. [But] the Court constantly expanded the cases eligible for the death penalty, so that the underlying premise for my vote has disappeared, in a sense. I really think that the death penalty today is vastly different from the death penalty that we thought we were authorizing.”

Justices Harry Blackmun and Lewis F. Powell, also from that 1976 court, expressed similar regrets over their vote to uphold capital punishment.

“I have come to think capital punishment should be abolished,” Powell was quoted in his biography. “I would vote the other way on any capital case.”

Justice Blackmun, even before retiring, in a dissent of Callins v. Collins in 1994, stated: “From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death … the basic question – does the system accurately and consistently determine which defendants ‘deserve’ to die? – cannot be answered in the affirmative.”

Indeed the “sufficient progress” in the equitable dissemination of capital punishment SCOTUS justices saw (or thought they saw) in 1976 was all smoke.

Today, African Americans comprise 14 percent of the U.S. population, yet 41% of those sitting on death row are Black, says the Death Penalty Information Center.

In 2004, William Henry Furman, whose life was spared by the 1972 decision, got in trouble again. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison for another burglary. He was paroled in 2016. That year, he told Reuters: “I still believe the death penalty is cruel and unusual punishment”.

He said this, too: “I can tell anybody who wants to commit a murder, ‘Leave it alone.’”

Furman is now 81 years old.

More columns by Roy S. Johnson

Bob Costas calls MLB Rickwood game ‘just perfect’, weighs in on what to call it.

I didn’t know my father long but he still makes me smile.

Plaintiff in historic SCOTUS case shed tears for late father after ruling

Alabama’s SCOTUS lawyer gets critical race history lesson, courtesy Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson

Through faith, former Birmingham news anchor finds unlikely new season as an actor