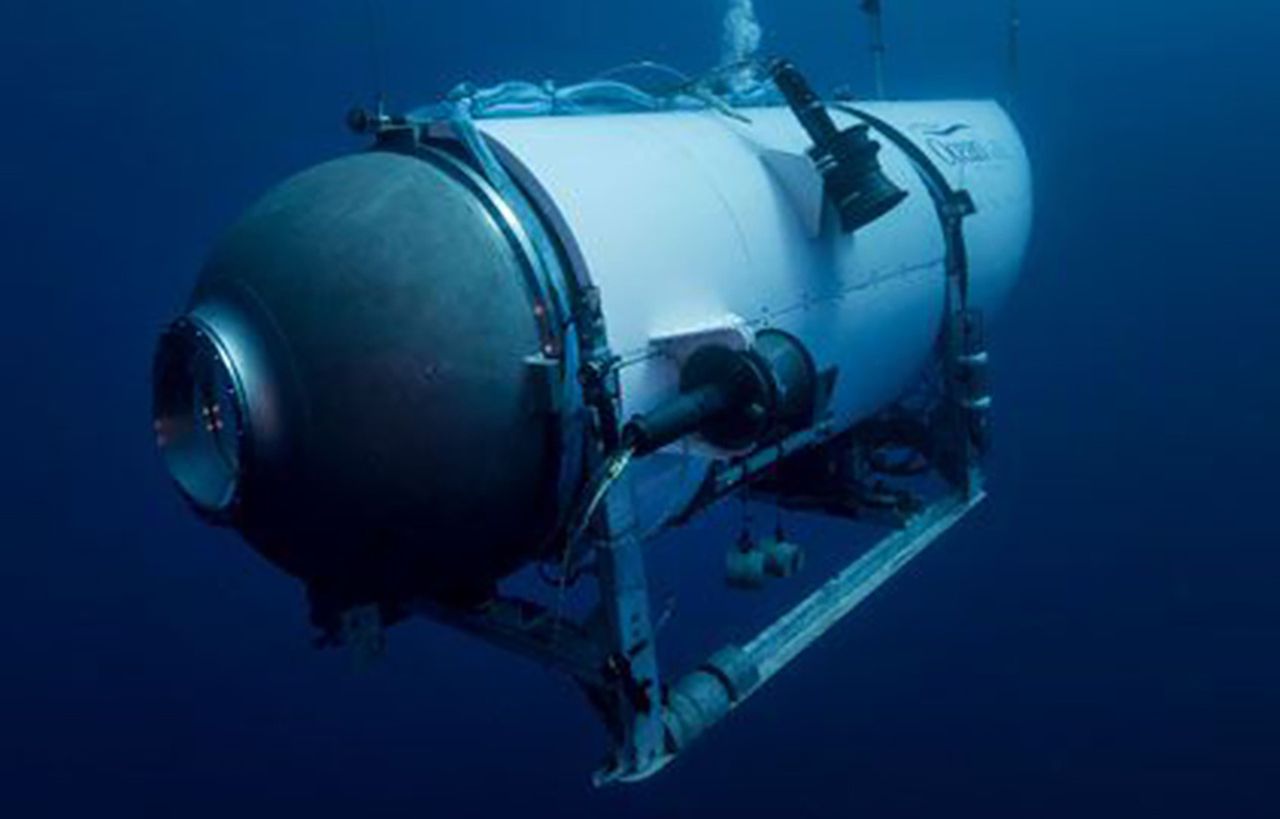

Missing Titanic submersible: Fewer than 30 hours left, underwater noise heard; What you need to know

The search for the missing research submersible, named Titan, that disappeared Sunday, continues Wednesday with fewer than 30 hours of oxygen remaining.

A Canadian military surveillance aircraft detected underwater noises as a massive operation searched early Wednesday in a remote part of the North Atlantic for a submersible that vanished while taking five people down to the wreck of the Titanic.

A source familiar confirmed to ABC News that there were reports of “banging” that were picked up by sonar in the search area on Tuesday morning, but nothing has yet been found.

A statement from the U.S. Coast Guard did not elaborate on what rescuers believed the noises could be, though it offered a glimmer of hope for those lost aboard the Titan as estimates suggest as little as a day’s worth of oxygen could be left if the vessel is still functioning.

“Those ROV searches have yielded negative results but continue,” the Coast Guard said on Twitter. “Additionally, the data from the P-3 aircraft has been shared with our U.S. Navy experts for further analysis which will be considered in future search plans.”

Here’s what we know as of Wednesday morning:

Who is on the submersible?

Stockton Rush, the CEO of OceanGate; Hamish Harding, a British businessman, pilot and space tourist; Paul-Henri Nargeolet, a French diver and Titanic expert; Shahzada Dawood, a Pakistani businessman, and his son Suleman Dawood.

‘A monumental task’

One of the best-case scenarios that might have happened to the Titan would be if it has been entangled in the wreckage of the Titanic, an ocean explorer and expert said Tuesday.

Tim Taylor, an ocean explorer and the CEO of Tiburon Subsea, told NBC News Now the best-case scenario is that the Titan would have been entangled in the wreckage

“Lifting the submarine off the bottom is not as hard or difficult as one may think if it’s still intact,” Taylor said.

It’s unclear what happened to the submersible, and searches are ongoing.

“You’re really fighting a clock here,” Taylor said. “They don’t have a lot of options. Every hour that goes by, their options get less and less. … This is a monumental task,” he said.

Who is helping?

Three C-17 transport planes from the U.S. military have been used to move commercial submersible and support equipment from Buffalo, New York, to St. John’s, Newfoundland, to aid in the search, a spokesperson for U.S. Air Mobility Command said.

The Canadian military said it provided a patrol aircraft and two surface ships, including one that specializes in dive medicine. It also dropped sonar buoys to listen for any sounds from the Titan.

In addition to an international array of ships and planes, an underwater robot had started searching in the vicinity of the Titanic and there was a push to get salvage equipment to the scene in case the sub is found.

The search for the missing vessel has drawn international attention. In Dubai, where the missing British adventurer Hamish Harding lives, Crown Prince Hamadan bin Mohammed Al Maktoum wrote: “Dubai and its people pray for their safety and hopeful return home.”

Were there warnings of problems?

Questions remain about how teams could reach the lost submersible, which could be as deep as about 12,500 feet (3,800 meters) below the surface near the watery tomb of the historic ocean liner. Newly uncovered allegations also suggest there had been significant warnings made about vessel safety during its development.

Documents show that OceanGate had been warned there might be catastrophic safety problems posed by the way the experimental vessel was developed.

David Lochridge, OceanGate’s director of marine operations, said in a 2018 lawsuit that the company’s testing and certification was insufficient and would “subject passengers to potential extreme danger in an experimental submersible.”

The company insisted that Lochridge was “not an engineer and was not hired or asked to perform engineering services on the Titan.” The firm also says the vessel under development was a prototype, not the now-missing Titan.

The Marine Technology Society, which describes itself as “a professional group of ocean engineers, technologists, policy-makers, and educators,” also expressed concern that year in a letter to Rush, OceanGate’s chief executive. The society said it was critical that the company submit its prototype to tests overseen by an expert third party before launching in order to safeguard passengers. The New York Times first reported about those documents.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.