Healing harmonies: the restorative power of Black sacred music

The first place Quita Tinsley Peterson learned about the healing power of communal care was in their rural church in Middle, Ga.

Hill Baptist Church is small, but four generations of their family were nurtured here. This is the spot where their great-grandfather went to school and where their grandmother and mother sing their gratitude to God. Some of Tinsley Peterson’s earliest memories were by their mother’s side in the choir stands. They were so small back then. They could barely peek over the pews. But the church helped them grow into roles that Tinsley Peterson held with pride like youth superintendent of the church’s Sunday school.

“It was actually a space where I was allowed to be a leader,” Tinsley Peterson said. “I think a lot of Black girls have experiences growing up where their leadership is being stifled. They’re not being encouraged to see themselves in that way. But at church, I was actually encouraged very much to be a leader – to do all the things. Hence, why I did so many things.”

One of those positions was the junior choir, which was central to their youth. Tinsley Peterson can almost list off Kirk Franklin’s entire discography and go into depth about the choral engineering of each track. They loved how the crescendo and decrescendo in “Now Behold the Lamb” made the song swell with emotion. How the different choral sections uplifted each other near the end of “Brighter Day.”

Being part of that magic is life building, they said. The sopranos’ falsettos intermingled with the altos’ warmth which supported the depth of the tenors and baritones. Their voices create a sacred space where collective suffering was the call and resounding liberation was the response.

Now 33, Tinsley-Peterson still taps into that sound as an activist in the reproductive justice space through their consulting firm, Iola Strategies.

“Something about the Black choir experience that really stands out to me is community – being in space created by us, for us. Being able to sing about joy, pain or struggle, and learning how we all have a role in supporting each other to create a beautiful sound together,” Tinsley Peterson said. “This is also true in organizing. As someone who does organizing, a key piece of organizing is showing people that we all have a role in the movements that we build. It’s just a matter of finding your role. And together, we create this beautiful collective.”

Quita Tinsley Peterson (left) sings in front of a congregation at Hill Baptist Church in Middle, Ga. Now 33 (right), Hill is a reproductive justice activist.

‘I’m Not Tired Yet’

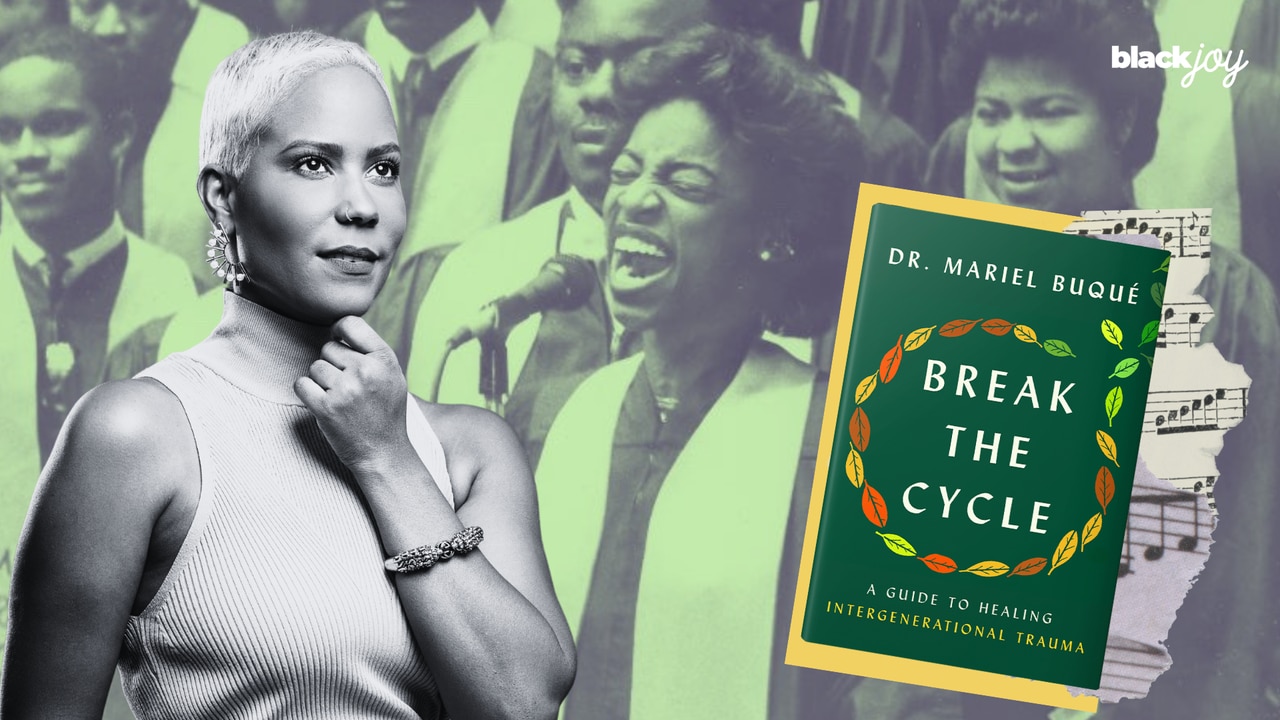

From the negro spirituals composed in secrecy during enslavement, to the civil rights anthems that declared “we shall not be moved,” to the gospel hits that erupt in a praise break of emotions within Black bodies to this day, Black people have been harnessing the communal healing of song for generations. Dr. Mariel Buqué, a psychologist and intergenerational trauma expert who authored the forthcoming book “Break The Cycle,” said multiple healing practices, like humming and rocking the body, are felt while both participating and witnessing choir and gospel music. Meaning the evolution of Black choral music not only sculpted the Black spiritual experience, it passed down the tools needed to heal our bloodlines.

“We have within the diaspora two very important elements of our history, which are intergenerational trauma, but also intergenerational resilience. They are always existing in our communities at all times,” Buqué said. “We can’t talk about generational healing without talking about the immeasurable resilience that has also been passed down, which has been exemplified in the ongoing confrontation of institutions that have perpetually traumatized us and reflected in the deliberate joy we have chosen to embody despite it all.”

Intergenerational trauma refers to how the psychological effects of one generation’s traumatic event are passed down to the next generation. The understanding of intergenerational trauma touches on the different ways the body archives memory. Buqué said that as we go through our lives, our bodies are depositing hormones in our bloodstream, thus recording the human experience on a cellular level. When a group of people encounter an acute, distressing event, such as genocide, poverty or abuse, their bodies are flooded with stress hormones which, when experienced chronically, can impact the genes inherited by their lineage.

Black people have endured a multitude of racial terrors that still sit in our bodies. It’s how the wail of a Black mother witnessing the death of a Black child at the hands of police echoes the grief of the enslaved mother whose child was snatched from her arms. It’s how the heaviness of discrimination can haunt a Black employee working in a predominantly white workspace.

“We carry memories that are from our lifetime. We carry memories that are from previous lifetimes,” Buqué said. “If I were to talk about the Black experience specifically, the intergenerational trauma and the cellular memory that is captivated in our bodies has a lot to do with systematized terror that has been there for centuries. So when you think about what happens to a body that is in a state of ongoing terror for the entirety of its life – and then for generations – you have to think about how much fear has been deposited in the cellular memory of a Black body. Anybody who is currently existing in a Black body is carrying a lot of the historical underpinnings of that biology with them because they’re also a byproduct of generations of that terror.”

Buqué has witnessed and studied the side effects of intergenerational trauma, first as a volunteer in her hometown of Newark, N.J. and then later during her clinicals at Columbia University’s Irving Medical Center. African Americans are at higher risk of heart disease, diabetes and stroke than white people. Buqué believes trauma plays a role in the health disparities because it shrinks a person’s window of tolerance, or the state where a person can thrive while still handling minor stress. Trauma also messes with the wiring of a survivor’s nervous system, making it harder for them to move from a state of fight, flight, freeze and fawn and to a state of rest and digestion.

“When a body is not able to rest for generations, is always on hyper alert, and is always perceiving a threat because there are real threats around, then that body is going to become vulnerable to stress,” Buqué said. “And the thing that we also have to consider with regards to neurons and the nervous system in the body, and the body being in chronic stress for decades and generations, is that eventually the body becomes profoundly exhausted.”

Time and time again Black people refused to buckle under that exhaustion of oppression. They’ve reclaimed their bodies through movement, voice and tapping into African traditions. The liveliness and hope of Black sacred music reminded Buqué of the atmosphere at Congo Square in New Orleans, where hundreds of enslaved and free Africans found economic and spiritual freedom during the 19th century as they sold goods and connected to their ancestry through dance.

“It’s where there used to be a lot of ways to connect to rhythm, dance, community, and communal healing and sound. It’s how we’ve been able to engage in a lot of the survival that we’ve had to enact in our Black bodies for many centuries,” Buqué said.

Over time, Congo Square became the birthplace of many of the Big Easy’s beloved traditions, such as the second line, New Orleans jazz and Mardi Gras Indian traditions. These sacred spaces of joy are vital to our healing, Buqué believes. Joy can help buoy people’s mood during heavy times. But it also has the power to restructure a traumatized mind.

“Our brains can be shifted and changed in a positive direction even if we’ve suffered in our lifetime and if people have suffered before us. So the thing about laughter and joy is that it actually creates different and more positive neural firing inside of our brains that connect to joy.” Buqué said. “It’s really important for us to take this into consideration, especially when we’re talking about intergenerational trauma, restructuring our genetics, and restructuring the ways we engage with our lived experiences within black bodies.”

“So the more that we invite in laughter,” Buqué advised. “The more comedies that you watch. The more you’re in community, having big-belly laughs – all of those experiences are creating neural firings that are basically helping you to heal and helping you create more experiences in your body that are programmed to heal.”

Dr. Mariel Buqué (left) is a psychologist and intergenerational trauma expert who authored the forthcoming books “Break The Cycle”

Lay down your burdens by the riverside

Protected by the brush of forest and under the cloak of night, the enslaved met in what were called “hush arbors” to commune through song and connect with the divine. Here, negro spirituals became a medium that purged them of their sorrows and made room for liberating joy. These meetings had to be clandestine in nature or they risked violence by their enslavers who forbade such gatherings in fear of uprisings.

But in the hush arbors and praise houses of the enslaved, the enslavers’ words held little power. Silvia King, a Moroccan-born woman who was enslaved in Texas, described the ecstatic nature of ring shouts during her 1936 interview for the Federal Writer Project’s Slave Narrative Collection. King mentioned these transcendent rituals where Black bodies could move freely until the break of dawn despite the realities of enslavement.

“De black folks gits off down in de bottom and shouts and sings and prays ‚” King said. “Dey gits in de ring dance. It am jes’ a kind of shuffle, den it git faster and faster and dey gits warmed up and moans and shouts and claps and dances. Some gits ‘xhausted and drops out and de ring gits closer.”

Buqué pointed out how multiple aspects of the Black spiritual experience mimic the body-based practices she incorporates in her own therapy sessions as she teaches clients how to disrupt the cycle of pain in their lineage. When trauma freezes us in states of anger, sadness or fear, movement can help us heal.

“When we shake the body or move trauma pockets out of the body, we shake up that trauma retention that we tend to keep whenever we have traumatic experiences in our lives,” Buqué said. “So, a lot of what is happening in the world of trauma is that we’re recognizing and integrating body-based practices into trauma work because we understand that a lot of what keeps people unwell is the fact that they have all of these experiences in their bodies where they feel inescapable.”

There are multiple ways to engage with somatic healing, with some practitioners offering trauma-informed yoga or dance therapy into their spaces.

“All of them have a very similar goal in mind,” she said. “Which is really to move the trauma out of the body and to help the person feel like their body is safe, and they have a safe place to exist in and not feel like they need to be afraid of their body and how their body is responding to their environment.”

Negro spirituals laid out the framework of Black sacred music both lyrically and somatically. The spirituals became anthems of liberation as the enslaved coded their music with messages that mapped escape routes to freedom. Their voices encouraged each other to lay their burdens down by the riverside of freedom and follow drinking gourds. They listened for the spiritual “Go Down, Moses,” which announced Harriet Tubman’s arrival as she guided enslaved people to freedom through the Underground Railroad. All these songs are in a call-and-response format — a leader sings a verse and a chorus of people answers them.

Black choral groups and musical directors carried on the tradition of negro spirituals as the tune of Black sacred music morphed gospel hits. The Fisk Jubilee singers brought the spirituals to national stage as the ensemble, composed of students from the HBCU Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn., pulled their college out of a financial crisis with a choir tour in 1871. Since emancipation, the McIntosh County Shouters have used the foot stomping, body-rocking, hand-clapping ring shout tradition to preserve their Gullah-Geechee heritage in Georgia. Thomas A. Dorsey invented the gospel sound during the 1920s and 1930s as his blues and jazz roots married spiritual messages.

As Black people continue the legacy of spiritual music, Buqué, who is also a sound healer, said the vibration of their voices were healing themselves and their communities.

“Humming is a practice that can actually help us feel rested and relaxed, and actually helps us to create a reset in our nervous system,” Buqué said. “So whenever we are in a church environment, and we’re either humming ourselves or we’re hearing the hymns and the hums that are coming from our community members, it’s creating for us this experience of feeling more at ease and more relaxed.”

Fisk Jubilee Singers (left) on a visit to England, where they where invited to give a concert before Queen Victoria. Front row, left to right: Jennie Jackson, Mabel Lewis, Ella Sheppard, Maggie Carnes, America W Robinson. Back row, left to right: Maggie Porter, E W Watkins, H D Alexander, F J Loudin and Thomas Rutling. Twelve Gospel Singers (right)Hulton Collection With Raised Hands Singing in a Church Service.

‘Imagine me being free’

Buqué experienced this restorative state during a recent church visit. She had just finished writing “Break The Cycle,” and was very attuned to the ways people incorporate healing modalities into their lives. During worship, she noticed something interesting. The loud music made their seats vibrate and the congregation was swaying and humming together.

Whenever Buqué is working with a client enduring chronic trauma, she makes sure to incorporate more than one healing practice into their treatment plan. The breathwork that soothes their nervous system is paired with the body movement that releases trauma from their bodies.

“I always layer the practice because we are working with so many layers of trauma. so when I was able to observe that in church, I was like, we’re working with the layers of healing here in the church environment,” Buqué said. “In addition to the spiritual piece, we have humming, we have rocking, and we have the sound frequencies vibrating our bodies and our bodies’ hormones and bringing them into a state of balance. I started thinking, ‘Wow. Like, has anyone been thinking about the fact that this is happening in a church environment? That part of the reason why we feel so at ease once we’ve transitioned from services is because we are literally being reset in this environment?”

This method of recalibration sticks with congregants whether they are in church or not. Quita Tinsley Peterson hasn’t stepped inside the sanctuary of their childhood church home since college. The same space that nurtured her leadership, tried to shrink their queerness during her teenage years. Outside of the church, Tinsley Peterson found more space to explore their sexuality. Tinsley Peterson no longer claims Christianity, and describes themselves as a spiritual person who prefers to connect with Earth elements and put their trust in the universe.

As an avid music junkie, Tinsley Peterson said they have multiple soundtracks for life. When the social justice work gets intense and they’re battling discriminatory legislation, their bad b*tch, goddess era playlist hypes them up. Summer Walker and SZA stay in their ears if they’re feeling sad. But when they’re wrestling with intense emotional overwhelm, they go back to their gospel music for a reset. Despite the wounding that happened in their church, the choir remains the place where they found the freedom songs.

One of those tracks is Kirk Franklin’s “Imagine Me.” It’s a song that hits differently now than it did back when they were dealing with the internal struggle of being queer in church.

Now it’s the song that reminds them to love themselves sacredly.

“When I was a young person, I was trying to trust the Lord and that He would save me from this identity or these urges that I felt like I was struggling with,” they said. “But as a queer adult who’s very happy and secure in their queerness, ‘Imagine me being free’ feels like I do feel free in my identity and who I am. I don’t necessarily trust like a Christian god, but I trust The Universe, that everything falls into alignment when I choose to move in alignment with myself.”