Alabama schools increasingly rely on emergency certified teachers

Amid teacher shortages, Alabama school officials are increasingly relying on alternative pathways to get teachers into classrooms, including certifying those with college degrees who want to teach but don’t have formal training in how to do so.

Statewide, 1,300 of the state’s 47,500 teachers, or 3%, were teaching using emergency certificates during the 2020-21 school year, the latest year for which school-level data is available. That’s more than three times the number of emergency certificated teachers from five years earlier.

State-level data the Alabama Department of Education provided to AL.com shows that number grew to 1,800 during the 2021-22 school year. It’s unclear whether the percentage of the total teaching force using emergency certificates increased.

The largest number of those emergency certified staff – more than 600 – are teaching in elementary school, positions that used to be easier to fill. Ten years ago, the state issued nine elementary-level emergency certificates.

The quality of instruction can be a concern for parents whose children are students of educators who haven’t learned how to teach. Jeffrey Wilson recently withdrew his 10th grade daughter from a business education class in Talladega County taught by a teacher with no training in how to teach.

Wilson said the teacher relied heavily on video instruction, a method that wasn’t working well for his daughter nor some of the other students. Ten of the district’s 500 teachers – 2% — used emergency certificates in the 2020-21 school year.

“My biggest thing was that you’re having kids fail where they’re not getting instructed,” he said.

Read more Ed Lab:

Talladega County Superintendent Suzanne Lacey said she has to rely more on emergency certification and people without traditional educational training, but her district does provide instructional coaches to work with all new teachers, fully-certified or not.

“We’re regularly, routinely supporting them with practices that would be effective in the classroom,” Lacey said, “[including] classroom management techniques, all of the things that we would do for any teacher.”

Other than hiring a long-term substitute, who are only required to have a high school diploma, superintendents have little option than to hire someone with an emergency certification and work to make them an effective teacher.

“We want to hire college graduates with a teaching certificate right out of college and they’re ready to go, hit the ground running,” School Superintendents of Alabama Executive Director Ryan Hollingsworth said. “But they’re not there. The colleges are not producing them.”

“Emergency certification is getting a bad rap,” he added. “What’s my alternative as a superintendent?”

A stop gap measure, or permanent solution?

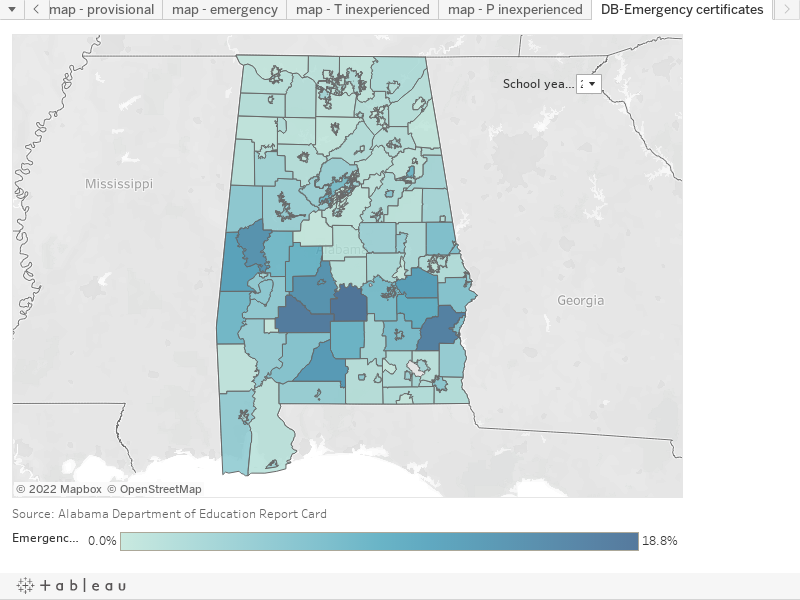

The 2020-21 school-level data shows suburban school districts like Homewood City Schools had no teachers using emergency certificates, but in rural Lowndes County, nearly 20% of teachers were emergency certified.

In Lowndes County, Central Elementary School, one of three preK through fifth grade schools in the district, had 42% of its teachers there under emergency certification during the 2020-21 school year.

Lowndes County superintendent Jason Burroughs did not return a request for comment.

Wilcox and Barbour counties – both with majority Black student populations – saw staff qualification rates similar to Lowndes, while Bibb and Autauga counties – both with majority white student populations – had fewer than 1% of teachers working under emergency certifications.

The number of emergency certificated teachers grew exponentially after lawmakers in 2019 acted on a recommendation to extend the time a teacher can teach using an emergency certificate from one year to four years.

State officials considered it a stop-gap measure, but it’s unclear whether the four-year allowance will be reduced any time soon.

The National Council on Teacher Quality recommends a one-year time limit for emergency certification, but Chief of Policy Shannon Holston said when that isn’t possible, states should limit the time to as short a period as possible.

“There’s a tension there,” Holston said, “and you want some flexibility to fill these really hard staffing challenges, but also is that person becoming a great teacher for your kid? Or are they just bouncing around district to district filling holes and not meeting the standards of the profession?”

Becoming a strong teacher is possible without traditional training, Council for Leaders in Alabama Schools Director Vic Wilson said, but school officials need structure in place to help them do so.

“It’s your [district] that’s going to coach them up,” Wilson said. “If you have someone that hires a non-certified person, throws them in the classroom and then just doesn’t check on him, or doesn’t offer the professional learning they need, then that’s kind of malpractice.”

Wilson said emergency certification is a good way into the profession in many cases. “You’ve got great teachers across this state who may have started in a non-traditional means,” he said.

That’s how Pamela Davis got started on her journey to become a teacher. Her college degree was in business, she said, but she always wanted to be a teacher. After working as a consultant in the computer information systems industry, teaching called her back.

“I started teaching as a substitute,” she said, and then worked her way to an emergency certificate.

At that time, in the early 2000s, to earn full certification on an alternate pathway, teacher candidates had to take college coursework in how to teach, which was expensive, she recalls.

Alabama now has multiple pathways to full certification, and an emergency certificate is where many start.

By 2007, Davis earned full certification and began teaching 6th grade math. She said her real-world experience brought a skill set to the school that most teachers hadn’t learned in teacher prep school.

“I was able to go in and analyze data, test scores,” she said, and design strategies using small groups and other skills she brought with her to teaching. “And I had those leadership skills already built-in that I learned in corporate America.”

Davis said she felt her real-world perspective, something traditionally-prepared teachers haven’t had a chance to experience, added value to her teaching. She is now an assistant principal at a Hoover middle school.

Davis’ is a success story, but it’s unclear how many teachers started with an emergency certificate, obtained full certification and stuck with the profession.

There are no state-level numbers showing how many teachers who start down the path of certification through the emergency path ultimately become fully certified.

District-level data showing the number and percentage of teachers using emergency certification for 2016-17 through 2020-21 (use the dropdown menu to view each year) is shown on the map below. Districts with a higher percentage of teachers using emergency certificates are shown in darker shades. Hover over the district for more information.

Click here if you are unable to see the map.