Maternal mental health care, support needed in Alabama, advocates say

Editor’s note: This story discusses mental health and data related to depression and suicide.

When Lauren Horn lost her second child to a miscarriage, she found herself battling the same postpartum depression and anxiety that she’d faced after her first pregnancy.

After she lost her child, whom she named Caroline, she still had many of the physical symptoms of pregnancy. Her hair fell out and her milk came in. She also faced intense nightmares, just as she had after the birth of her first child, several years earlier.

“I would be holding my dead baby, trying to like, bring them back to life, like doing CPR and trying to get help,” Horn said.

But, unlike a previous pregnancy and birth, when Horn also struggled with depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation, after her miscarriage she had access to a program through her OB-GYN’s office, which is one of four enrolled in the Previa Alliance program. She said the support and resources help her manage her symptoms and get help when she needs it.

Read more: Moms in Alabama say they need more help with breastfeeding, paid leave.

Previa was launched by Sarah Parkhurst, a Birmingham-based mom who dealt with postpartum depression herself. Currently, it serves about 200 women in the Birmingham area, but Parkhurst said she’d love to expand across the state.

Postpartum depression and anxiety are relatively common. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1 in 8 people who have recently given birth experience postpartum depression symptoms.

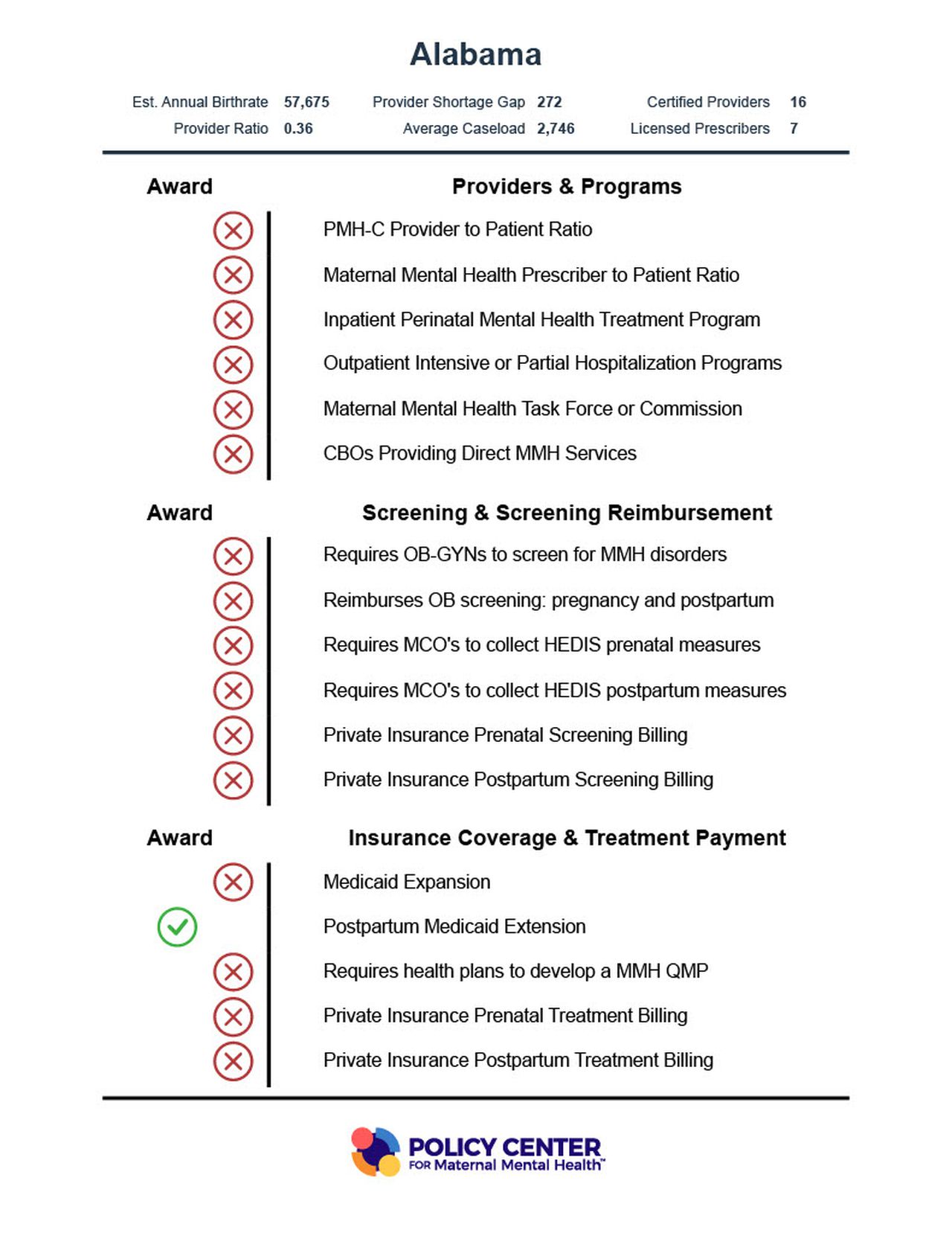

But many new parents struggle to get the help they need. According to inaugural Maternal Mental Health State Report Cards, the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health gave Alabama a failing grade relating to mental health support. Out of 17 awards for supportive structures, Alabama received one.

The 2023 Alabama Maternal Mental Health State Report Cards from the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health in collaboration with George Washington University. Courtesy of the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health.

“I think at this point, most people do recognize that our maternal mortality rate here, especially for women of color, is the highest in the developed world and people recognize that it’s only getting worse,” said Caitlin Murphy, one of the lead researchers on the report. “But I think there has been less attention to the fact that maternal mental health conditions are the number one factor contributing to maternal mortality, and that is primarily through suicide and overdose.”

Finding help can be difficult

After Horn gave birth to her son four years ago, she found herself overtaken by depression and anxiety.

She avoided seeking therapy services for some time, primarily because she was unaware that her symptoms could be indicative of postpartum struggles. She pushed through thoughts that her family would be better off without her and that her son deserved a “better mom.”

Even when Horn decided to seek help after experiencing recurring nightmares, she struggled to actually find a mental health provider who would take her insurance. Once, after finally finding someone in-network, the provider she was scheduled to see left the practice altogether. It took her about 18 months to start receiving regular care.

Once she did decide to seek help, Horn said she questioned whether the problems she was experiencing with finding a provider meant that she was “not fixable.”

“I was like ‘You know what? I guess I’m just psycho, and maybe I don’t need help, or maybe it’s all in my head. I don’t know,’” she said. “‘No one seems to be feeling the feelings that I’m feeling after having a baby.’”

Other moms might also have difficulty finding care – Murphy said that, in addition to a lack of screening and diagnoses of mental health disorders, many moms aren’t receiving the treatment they need.

“We know that over half of maternal mental health disorders are going undiagnosed. We know that treatment is not occurring,” Murphy said. “We know that over half of maternal mental health disorders are going undiagnosed. We know that treatment is not occurring.”

In recent years, maternal deaths have climbed across the country.

Black women are also more likely than white women to die during or within the first year after a pregnancy. In 2020, maternal mortality occurred at a rate of 55.3 deaths per 100,000 live births for Black mothers, compared to 19.1 for white mothers. The disparities in death rates increase with age – for Black mothers 40 and older, the death rate was 263.1, compared to 96.8 for white women in the same age group.

Read more: North Alabama woman charged with homicide after authorities say her meth use led to stillborn baby.

Read more: New Alabama maternal mortality report highlights preventable deaths, substance abuse.

Read more: Birmingham doula group to help more mothers tackle pregnancy, parenting.

Alabama’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee has released two reports since its creation. Substance use disorders or using alcohol or drugs were among the three leading causes of death among 80 deaths between 2016-2017 that occurred during pregnancy or up to one year after.

Experts say that many deaths, including those related to mental health, are preventable.

About two-thirds, or 67.5%, of Alabama mothers who died within a year of giving birth were enrolled in Medicaid.

The Maternal Mortality Review Committee recommended the expansion of Medicaid in their report; Alabama is among only ten states that have not expanded Medicaid.

The state has extended postpartum Medicaid coverage to last for up to a year after giving birth – the only mark on the report cards for which Alabama received an award.

In a report looking specifically at 36 pregnancy-related or associated deaths that occurred in 2016, five were determined to be suicides.

“We see most of the postpartum suicides occurring in the late postpartum timeframe, six to nine months postpartum, so the question is why during that time frame, what has changed? Or has mom just reached the end of her rope? You know, going without sleep can be extremely debilitating, right?” said Adrienne Griffen, the executive director of the Maternal Mental Health Leadership Alliance.

Murphy said that therapy in general can be a great tool for moms who may be struggling, but it’s most helpful when they have access to a therapist or counselor who is specifically certified in treating perinatal mental health struggles.

In the policy center’s reports, they classified specialized providers as:

- Providers who have received a Perinatal Mental Health Certification (PMH-C) from Postpartum Support International

- Providers who are qualified medication prescribers, such as psychiatrists, nurse psychiatrists, some certified nurse midwives and others who are registered with PSI as having received some kind of perinatal mental health training

Across the state of Alabama, there are 21 perinatal mental health providers, for a ratio of specialists to patients of 0.36.

In the U.S., the only state that had enough perinatal mental health specialists to meet the needs of patients was Montana, Murphy said.

“I don’t think there’s enough knowledge out there as well of the need for these specialized providers and specialized treatments, and that the lack of access to this specialized treatment is really continuing to drive the lack of access to services, and then unfortunately, maternal mental health conditions that can result in suicide,” Murphy said. “We see increasing these ratios as absolutely essential.”

She added that Alabama could take several steps that would be beneficial for moms that struggle with their mental health after pregnancy, including adding more maternal mental health providers and programs across the state, promoting community-based resources, requirements for screening for maternal mental health disorders and reimbursement for those screenings.

Improving access

Parkhurst said she started the Previa Alliance because she felt there was a lack of knowledge in her area when it came to postpartum mental illness, along with a lack of access to care. She launched the program in February 2022 and has been working with specific OB-GYN offices as it grows.

OB-GYNs who are enrolled in the Previa Alliance program can refer their clients to a HIPAA-compliant website, where they are screened for mental health struggles. If their scores indicate they’re struggling, Previa helps to connect them with a contracted maternal mental health professional in their area within two days.

Parkhurst and her team use an online scheduling tool to set up the appointment for the mother, then she constantly follows up with moms to make sure their needs are being met, she said. The providers work with Parkhurst and her team to ensure the mom’s insurance will work with their services – Parkhurst calls it “a circle around mom.”

Previa also has a digital library of evidence-based videos and learning tools created by licensed professionals, and Parkhurst hosts a podcast as well.

She hopes to expand the service to work with Medicaid and offer it to women across Alabama. Currently, Previa doesn’t charge OB-GYNs to participate, nor are women charged for screenings or access to the digital library.

“Some people have been like, ‘So why don’t you use direct-to-consumer?’” Parkhurst said. “I’m like, ‘How is that fair that this mom, because she can pay for it, gets education? She knows what it is, she can get therapy easily. And this mom, who probably honestly needs it more, can’t? I can’t do that.”

Horn said she doesn’t know where she would be if she hadn’t had access to Previa’s services. She said it eliminates the embarrassment of having to share intrusive thoughts when asking for help.

“I love that it’s offered to me – it’s a wonderful resource. I hate that it’s not offered to all women in Alabama – well, really, across the country, but especially in Alabama,” Horn said of Previa.

The Policy Center on Maternal Mental Health has put together a roadmap to improve maternal mental health, as well as guides for recommended state policies.

They’re also crafting a list of community-based organizations that offer maternal mental health services. The organizations must be registered 501(c)3s offering maternal mental health services to the perinatal population, including talk therapy, support groups, or other services specially serving mothers’ mental health during pregnancy or postpartum, Murphy said.

For Horn, who would have delivered this month, some days are better than others, but she said her faith and her work in therapy are helping her find peace. She said she’ll continue talking about her challenges with postpartum depression and anxiety if there’s a chance to shine a light on postpartum mental illness, even if it’s uncomfortable.

“If I’m able to help people, because of struggles I’ve been through, it’ll be worth it to me,” she said.

If you are struggling with suicidal thoughts or a mental health emergency, call 988 to connect to the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

New parents who would like to use the unlimited 24/7 Maternal Mental Health Hotline can call or text 1-833-943-5746 (1-833-9-HELP4MOMS).

To reach the Crisis Text Line, text HOME to 741741.

A list of crisis centers in Alabama can be found here.