New documentary tells the story of Daniel José Carr, Birmingham Jazz History

Trumpeter Daniel José Carr doesn’t speak much on stage during the Tuesday jazz jams at True Story Brewing.

But one evening in April, after the opening song, he had a few words for the audience.

“Welcome to the True Story Jazz Jam,” the Ensley-born musician said, as he leaned into the microphone. “We do more playing than talking. If you ever go to a jazz jam and they’re talking a lot, they probably can’t play and need to shut up.”

He continued as a few people at tables let out a light chuckle.

“Everything is improv. No rehearsal. We’re just going to keep the music happening,” he said. “If you can’t play the blues, you can’t play jazz. All this new stuff going on. We’re playing the real deal. We’re swinging over here.”

Almost immediately, he cued up his fellow musicians to play the John Coltrane quartet version of “Nancy (with the Laughing Face).”

Anyone who’s met Daniel José Carr knows he’s a straight shooter, both on and off the stage. That ethos, as well as the Tuesday jazz sessions, are the crux of “So You Say You Play Jazz? José Carr’s True Story,” a forthcoming new documentary from BellisarioSonic Arts.

Directed by Matthew J. Bellisario, the 75-minute film offers a glimpse into Birmingham’s live jazz scene through the eyes of the celebrated music educator, band leader and Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame inductee.

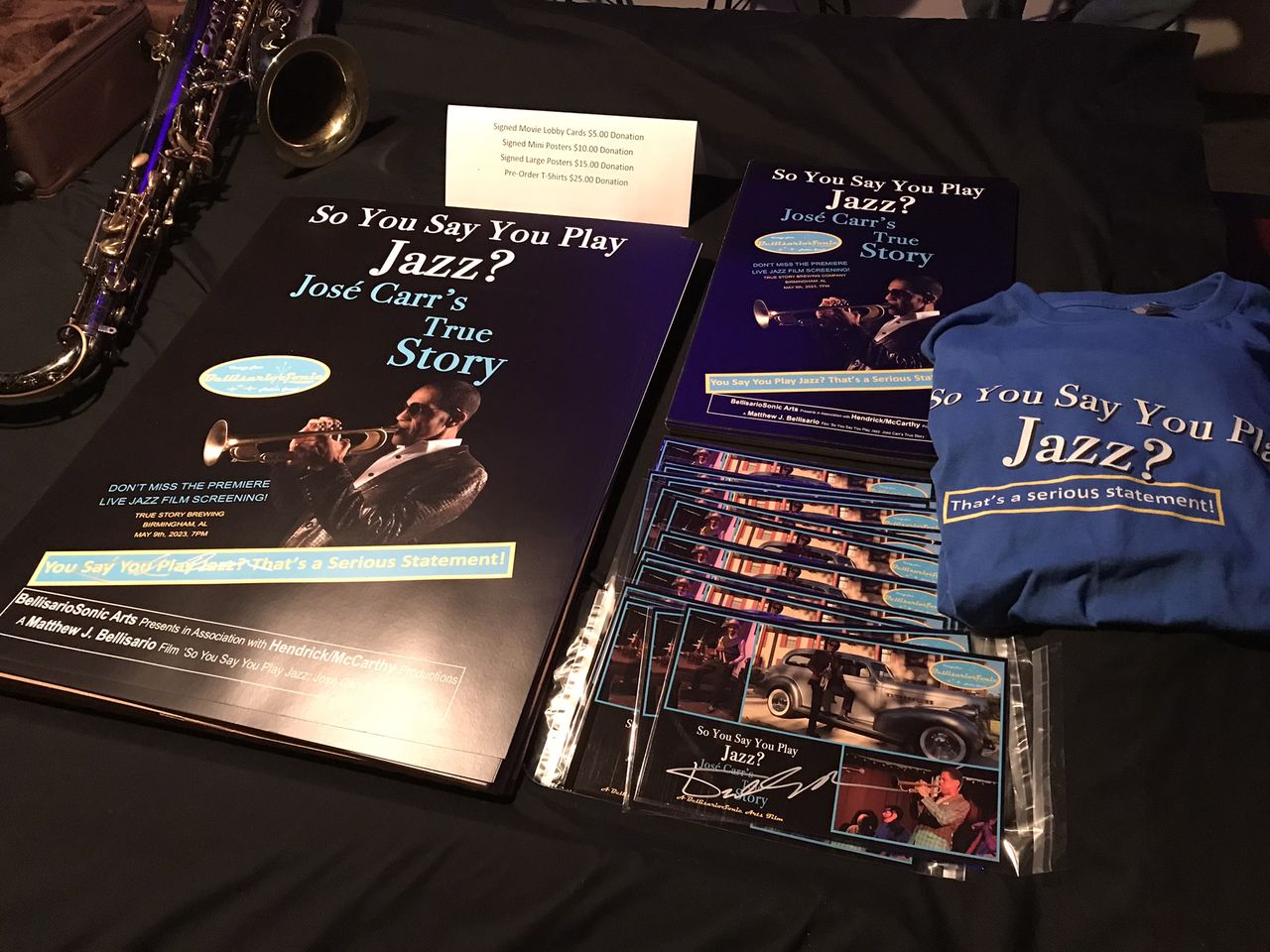

Posters and T-shirts for “So You Say You Play Jazz? José Carr’s True Story” at True Story Brewing. (Shauna Stuart| Al.com)

Bellisario, who works as an engineer at EWTN in Irondale, is also a guitarist and singer who has played his all of his life. “Jazz, rock, and a lot of blues,” Bellisario said. He’s also done a lot of his own recordings. Two years ago, Bellisario created BellisarioSonic Arts, a small media company to house his production ventures and music commentary.

In 2021, he showed up at True Story Brewing on a Tuesday night after he saw a sign outside of the Crestwood brewpub advertising the jazz jam sessions. Bellisario initially expected a night of “smooth jazz” or the contemporary jazz he’d become used to seeing at live venues over the years — covers of songs that aligned more with funk and R&B than traditional jazz music steeped in the blues.

But when he walked into True Story, he heard swinging and jazz standards with up-tempo beats, chord changes, and improvisation. He saw Carr, dressed to the nines, onstage with musicians waiting their turn to sit in.

The weekly jazz jam at True Story Brewing in Crestwood is on Tuesday evenings (Shauna Stuart| Al.com)

“When I saw them play, I thought, this is going back to the 40s and 50s. To Bebop. That’s what I love. I have a huge record collection of that kind of music and I was just blown away that they were playing that stuff here,” Bellisario said. “That’s actually a crux of the documentary story. Running across that. And finding this hidden gem.”

When Bellisario approached Carr at True Story, they started talking about jazz musicians, including trumpeter Lee Morgan, one of Carr’s favorite horn players. Bellisario eventually pitched the idea of shooting a documentary. While Carr was surprised, he was on board.

Musicians come from around Alabama and across state lines to sit in at Daniel José Carr’s Tuesday night jazz jam at True Story Brewing. (Shauna Stuart| Al.com)

Bellisario got to work putting together a team– a small group of volunteers with experience in television broadcast production, including producers Greg Hendrick and John McCarthy. Next, they started interviewing people. Naturally, they spoke to the core group of musicians who took the stage every Tuesday, including Carr, trumpeter Collins “Bo” Berry, keyboardist Willie Jackson and bassist Bernard McQueen.

Some of the interviews were happenstance — people the team met in the audience on Tuesday nights. They spoke to documentary photographer Cassandra Griffen, whose noted subjects include civil rights leader Fred Shuttlesworth as well as blues musician Gip Gipson and jazz bandleader Sun Ra. Also on the rundown, music historian Burgin Matthews — founder of the Southern Music Research Center and author of the biography “Doc: The Story of a Birmingham Jazz Man” and the upcoming book “Magic City: How the Birmingham Jazz Tradition Shaped the Sound of America.” The team did most of the interviews at True Story, but they did go offsite, driving 15 minutes to Ensley, the Birmingham neighborhood where Carr grew up. They also drove to the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame in Birmingham’s historic 4th Avenue Business District to interview the executive director Dr. Leah Tucker.

The team spent more than a year-and-a-half shooting and editing the documentary. Based on the trailers, the result is a critical look at the past, present and future of the jazz scene in Birmingham. Watch below.

“Jazz, blues, it all played a huge part in getting us through that civil rights movement,” Griffen says in an interview featured in the trailer. In another, Carr laments the lack of live jazz venues in the city. “A weekend in Birmingham, there’s nowhere you can go hear no jazz. Not one place” says Carr.

“Birmingham has this jazz history that is really distinctive, unique, and important, I think, José, but unknown,” Matthews told Carr during a conversation in the Carver Theater at the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame.

“There are a lot of band directors that say ‘I have a jazz band’, But if you listen to what they’re playing, it’s not really jazz,” Berry said while seated next to McQueen during an interview at True Story.

“So You Say You Play Jazz? José Carr’s True Story” will premiere at 7 p.m. on Tuesday, May 9 at the weekly True Story Brewing jazz jam (following about an hour of music, the crew will screen the documentary around 8 p.m.) Bellisario hopes to eventually host both private and pubic screenings around the city, including a showing at the historic Carver Theater and Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame.

“José is the central figure in basically showing how important the live jazz jams are to keeping jazz going. Not only for musicians and for people coming to learn about it,” Bellisario said. “But (for) the hidden history of jazz in Birmingham. That’s part of the documentary as well. And also José telling us about the history of jazz in Birmingham. So, it’s kind of tied together.”

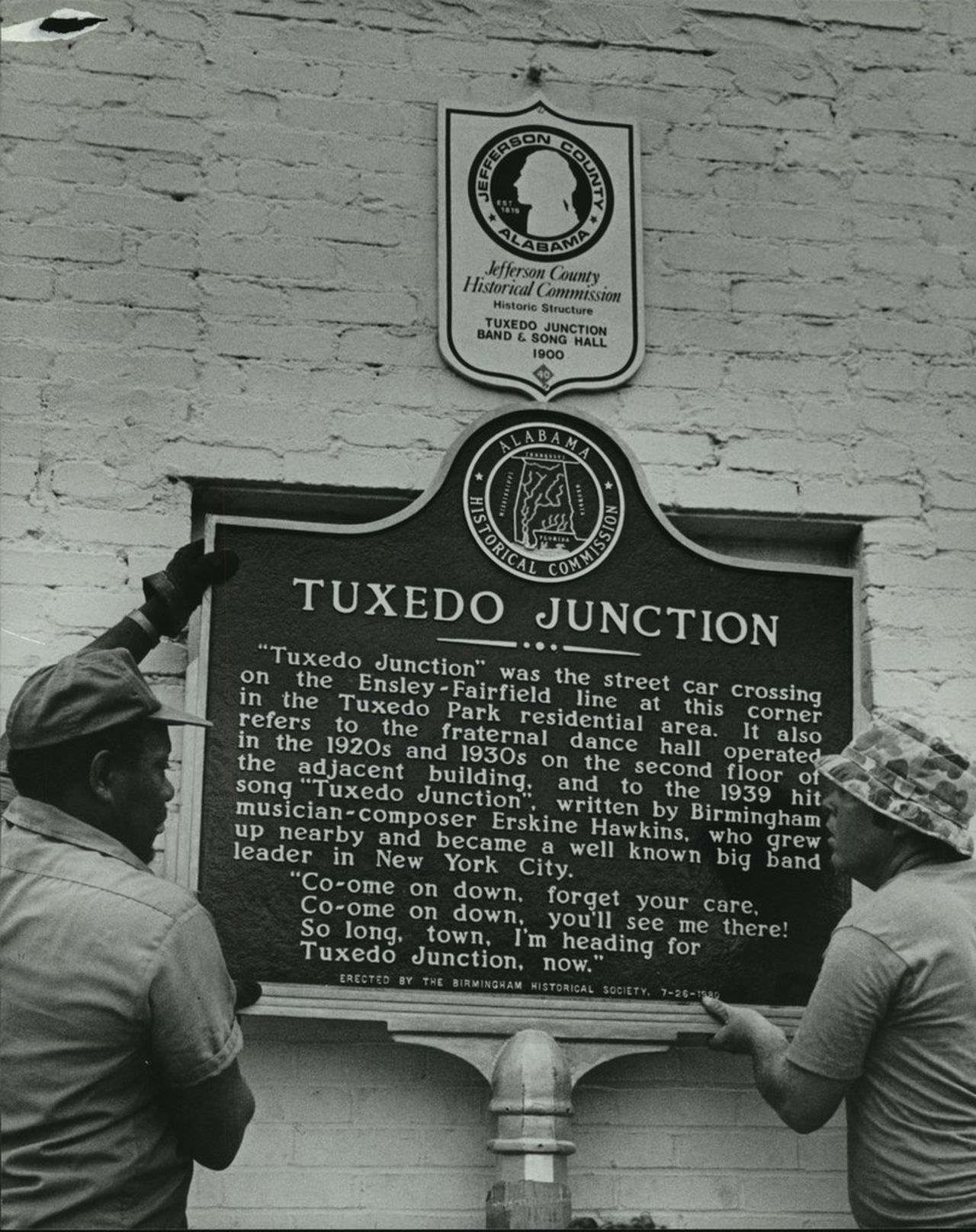

Birmingham has birthed — and hosted — a number of jazz icons. Ensley, in particular, was once home to the renowned Tuxedo Junction, a jazz club and social hub for the city’s Black nightlife during the 1920s, 1930s,and 1940s. In 1939, Birmingham jazz trumpeter and bandleader Erskine Hawkins released a song devoted to the club’s namesake.

Fourth Avenue Business District– the historic Black business district– was a beacon for legends. Duke Ellington and Lionel Hampton played the stage at the Carver Theatre. Across the street, Ellington and Count Basie regularly performed in the 1,500 seat auditorium and grand ballroom in the Colored Masonic Temple.

READ: The sounds of 1920s jazz in Birmingham Birmingham

30 Alabamians who changed jazz history

From the early 1990s to the 1950s, bandleader John T. “Fess” Whatley led the music program at Parker Industrial High School. Alums of the program went on to play in bands for Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday. Birmingham jazz icons Sun Ra, Erskine Hawkins, Sammy Lowe, Paul Bascomb, Dr. Frank Adams, Sr., Haywood Henry, Tommy Stewart and Cleveland Eaton were all students of Whatley.

Matthews’ Southern Research Music Center has a collection devoted to historic photos of Birmingham jazz musicians. Birmingham trumpeter Joe Guy was married to Billie Holiday. Guy was also best friends with trumpeter and educator Richard Clarke, the father of Birmingham city councilwoman Carol E. Clarke. The Clarke family has a storied legacy of musicianship in Birmingham. Richard and his brothers Pete, Charles, and Arthur, played in bands for a number of legends, including Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. While their sister Mary Alice Clarke Stollenwerck tried to avoid the label of a jazz musician, she was a pioneering performer in Fess Whatley’s Sax-o-Society.

Workmen unveil a marker commemorating Erskine Hawkins and Tuxedo Junction’s musical heritage. (AL.com file)

Carr describes himself as a late bloomer to the jazz scene. It’s a modest label, but he uses the term to describe his career transition. The Ensley-born trumpeter attended Council Elementary School, then later went to Jackson-Olin High School.

“I was listening to jazz back then, but my mind was not serious. I was playing R&B and all that stuff. But I always hung around cats that played the music,” Carr said. “At school, the older guys would come back and see the band director and I would have a chance to meet them. They was real good players.”

Carr attended Alabama State University in Montgomery. In the ‘30s and ‘40s, the school was regarded for its esteemed jazz programs — The Bama State Collegians, The Revellers, and The Cavaliers. The programs were so popular, in fact, that when ASU suffered severe financial hardship in the 30s, the three programs played at a number of balls and parties to generate revenue to help keep the school open. But by the time Carr joined the freshman class, ASU was better known for its marching band.

“So I started seeking jazz by myself in the city. I started playing by ear,” Carr said.

He continued studying jazz at North Texas State University, but he says he really learned to refine his technique from the Alabama-born musicians who developed careers in New York and Chicago.

“They were from Birmingham, but when they were older, they came back here,” said Carr.

“They’re gone now, but they’re the ones who bought me in and talked about music. About the jazz. The jazz character and the attitude and all that. That’s what got me involved in jazz.”

Carr always had a full-time job, so he couldn’t travel around the country as a touring musician. He got serious about practicing his jazz repertoire in the late nineties.

“I was good enough to play locally. But nationally, I was a below-average trumpet player,” said Carr, chuckling. “There were others who played for a living. They were putting their time in to be better.”

But, to his credit, Carr always hung out around older players. He said while a lot of his peers have died, he’s grateful to trumpeters Tommy Stewart, “Bo” Berry, and Jothan Callins — three elder statesmen of the Birmingham jazz scene — for helping him come into his own.

Trumpeters Daniel José Carr and Collins “Bo” Berry. (Shauna Stuart| Al.com)

And while he didn’t become a full-time touring artist, Carr himself is a renowned educator who taught marching band and classical music, helping students develop their skills on the bassoon, saxophone, and drums.

Carr, who led the band program at Bush Middle School and Jackson Olin High School, is one of the most popular and revered band directors in the city. Some former students refer to him as a “real-life superhero.” He was inducted into the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame in 2014. He’s also the institution’s director of music education, a position he’s retained while the hall is closed for renovations.

The Ensley native and his quartet have graced festivals, performance halls and venues around the city, from playing at popular bars to leading the second-line-inspired procession at the Mayor’s Masked Ball. But the trumpeter is probably most famous for the jazz jam sessions he’d lead around the city. For 10 years, Carr and his quartet hosted a weekly jazz jam at B.O.S.S. Ultra Lounge on Birmingham’s Southside. But the sets ended in early 2020, right before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2021, Margaret Walter-Wilson, a longtime listener, told Craig and Anna Shaw, the owners of True Story Brewing, about the former sessions at B.O.S.S. The brewpub hosted rock n’ roll sessions and art shows, so Wilson inquired if the duo would be interested in being the new stomping ground for a nightly jazz jam.

Carr remembers being dubious about the idea at first. “When I went down there, I said ‘Hey, you sure you want me to play here?” Carr said, laughing. “You know, ‘cause the place was kind of rugged.”

But the Shaws were enthusiastic and it was settled: Daniel Jose Carr’s weekly jazz jams had their new home. Fast forward to 2023– the music is still swinging.

“We hit about a year and a half a couple weeks ago and we ain’t stoppin’!’” Carr said.

On Tuesday evenings before the sets start, musicians gather around the tables at the brewpub, shooting the breeze before they take the stage flanked by a True Story Brewing banner and an Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame poster.

The first set of the evening always features the quartet. But it’s usually a short set — the night will include a run of jazz standards from Coltrane’s “Giant Steps” to Miles Davis’ “Solar.”

“I’m not selfish with the music,” Carr said. “If I have musicians come in that can really play, they don’t have to wait to play.”

Musicians come from all over the state — including Huntsville to Montgomery — and even across state lines from Florida, to sit in. Carr is inviting, but his standards are high. “Nobody should sit in and play just because they’re new. I tell them what the deal is,” he said. “But basically, they have to have their stuff together.”

“Some guys that play (at my set), they’re just barely getting by. I just don’t say nothing about it. Some guys come in and they don’t play good. And they know who I am. I’m very outspoken.”

A staunch educator, Carr is an advocate for younger musicians.

“If you’re a high school student, I’ll give you the benefit of the doubt. But you’ve got to be studying, too, at the same time. You just can’t jump up there and play and ain’t put no time in.”

Well-known and social, Carr will sometimes make the rounds at True Story. But other times, he’ll sit next to the stage and observe. And if a player isn’t up to snuff, he’ll critique them at one point during the night.

While the musicians enjoy the weekly sessions, Carr hopes to get more support from people in the city. The sets have regular patrons, but he’d like to see more people in the room, especially since there aren’t many venues in the city that routinely offer traditional jazz music (with the Carver Theater still under renovation).

The new marquee at the historic Carver Theatre, which houses the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame (Shauna Stuart| Al.com)

He knows about some newer spots in the city but said they cater to smooth jazz.

For those who might wonder about the difference between the music forms, Carr offers an example: Think about listening to Marvin Gaye’s song ‘What’s Going On?” but only an instrumental version. “It’s played with an instrumental…with just a saxophone playing,” he said. “That’s smooth jazz. Smooth jazz is nothing but R&B, but it’s played instrumental. It ain’t no jazz. I’m not knocking it, but it ain’t no jazz. I ain’t knocking the other music because I’ve played it before. But be-bop jazz is different.”

While Carr said there’s nothing wrong with smooth jazz, traditional jazz — particularly the Black cultural legacy of the art form — is dying in the city without the venues to both host current fans and cultivate a new generation of listeners.

“This was a town where musicians came to make a living. Until it just changed,” said Carr. “You don’t find a lot of people like me. Because I was baptized with the guys and grew up about 14 or 15.”

Carr said his mission is to keep jazz alive in the city of Birmingham, from preserving the history to mentoring the jazz musicians that will inherit the city.

“I’m the only one playing jazz in Birmingham because people who own the spots don’t want to take a chance and do it. They don’t want to take a chance to play the music,” said Carr.

“Most guys had to play all kinds of music because of their financial situation. I’m playing music for the cause. I’m trying to keep this alive. This is my true story,” Carr said of the upcoming documentary. “You say you play jazz…that’s a serious statement. Because ain’t too many jazz musicians around because they don’t want to pay the price. You’ve got to put the time in. If you don’t put the time in, you won’t be successful.”