Ghost of Legislature’s Past haunts Kay Ivey’s “education” budget

This is an opinion column.

Gather around the campfire, kids. I’ve got a ghost story to tell — about a mischievous spirit that still haunts the Alabama State House and a governor who doesn’t know her education budget is already dead.

It had been a long time since I had a call from my friend Mac Parsons, probably because he died about 10 years ago.

But lately — after an Alabama governor has recommended spending hundreds of millions from the Education Trust Fund on a water park, prisons and a shopping list of other things that aren’t schools — I’ve sometimes caught myself looking over at my phone.

What would the old curmudgeon say?

Calls from the circuit judge were an irregular but common thing. Always out of the blue. Never did he start with a “hello” or a “this is Judge Parsons” but only a gruff voice getting straight to it.

“You know what would make a good story?”

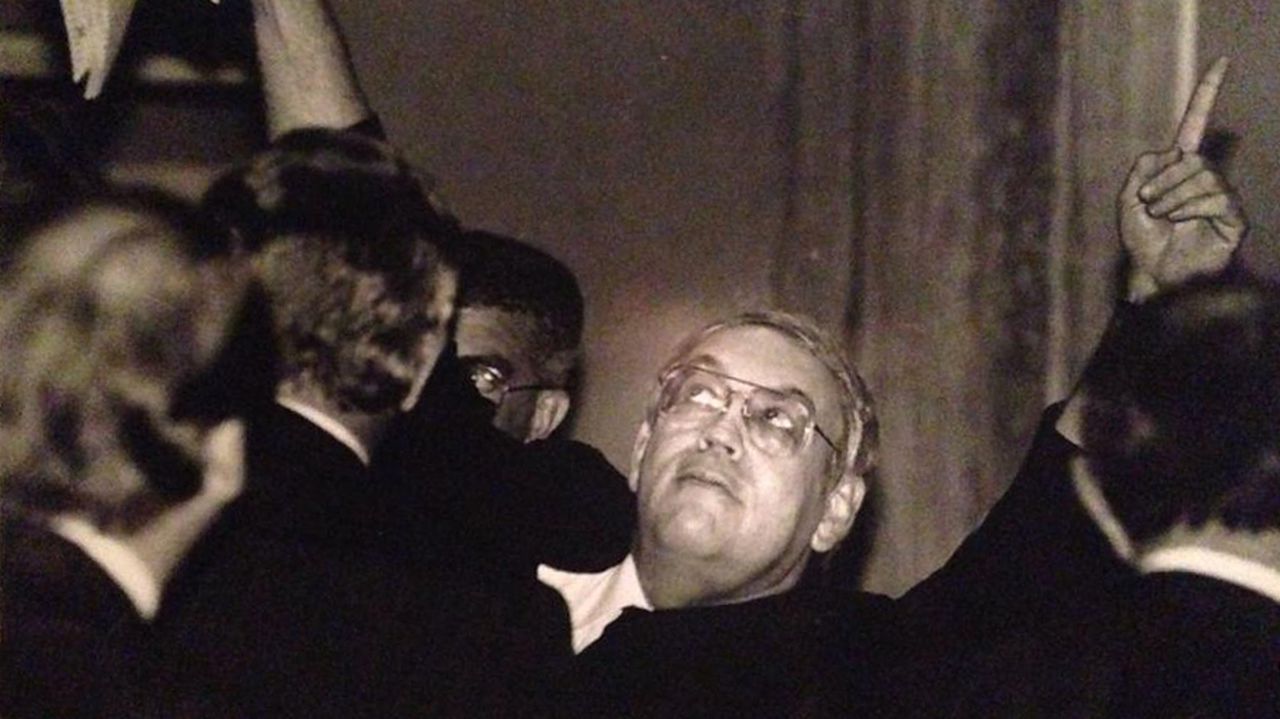

Parsons had served in the Alabama Legislature where he irritated his fellow lawmakers, exposing their schemes and lampooning their antics.

Once he sent out invitations to a $500-per-seat fundraising reception to “friends of Mac Parsons or those who would like to be friends of Mac Parsons” with a 10 percent discount for anyone paying cash at the April 1 event.

It was an April Fools Day joke, of course, but it also sent a message to his colleagues: Everybody can see what you’re doing.

“All these legislators go to Montgomery,” Parsons said. “They put their hands on the Bible and swear to uphold the Alabama Constitution of 1901 — and they haven’t read either one of them things.”

His quixotic crusades in Montgomery earned him accolades and nicknames from statehouse reporters and columnists — “Mac the Knife,” the “Goat Hill Guerilla,” the “Gadfly of Montgomery” and the leader of a pack of contrarians called “the Contras.”

One night the statehouse security locked Parsons outside when he’d stepped out to smoke. Lawmakers were meeting inside and Parsons didn’t think it was an accident. He kicked through the glass door and let himself back in.

Eventually, Parsons became such an annoyance, the Legislature drew him out of his district to ensure he’d never win again.

But the source of his influence was never public office nor political power, it was phone calls to people like me. We were kindred trouble-making fools with similar goals — to shine a light on Montgomery and shame it when it didn’t serve the people first.

Nearly every legislative session, I wonder what the old judge would think of things.

Things like a governor directing education dollars to things that have nothing to do with education, including $25 million for a Montogmery water park.

Then, out of the blue one recent afternoon, the phone rang.

“I’ve been reading what you’ve been writing,” the voice on the other end said. “There’s something important you missed.”

Easy shortcut

The voice on the phone wasn’t Mac speaking from the other side, but perhaps the closest thing to it. The call came from his old law partner, Judge Pete Johnson, who shares our old friend’s knack for troublemaking.

“They tried this already,” Johnson said. “Mac Parsons sued them, and if I’m remembering right, he went to the Supreme Court and won.”

When Gov. Kay Ivey recommended spending more than $300 million of education dollars on things that had nothing to do with education, at first I made an assumption: If this were legal, somebody would have done it already.

The Education Trust Fund is too big for someone to never have tried to raid it before.

I dug a little deeper. I went back to the law that created the Alabama Education Trust Fund in the first place and dang if it didn’t lay it out in plain language: The ETF was for “educational purposes only,” the law said.

That seemed clear enough, but often Alabama lawmakers just don’t care what the law says. They’ll try anything and see if it sticks. Governors, too. And laws are only as hard and fast that the courts that apply them.

But as it turns out, this sort of thing had happened before, only an old friend had stood in the way.

Johnson’s memory was mostly correct, but the details matter, especially when they’re funny.

Court records and news stories from 1987 and 1988 show this indeed has happened before.

Idled hands

In 1986, Parsons had backed Jim Folsom Jr.’s opponent for lieutenant governor. Folsom won anyway, and he retaliated by stripping Parsons of most of his committee assignments, much to the delight of other lawmakers.

Parsons took it as a challenge.

“I’ve said this and people take it jokingly, but without any really substantive committee assignments, I’ve got the time to pursue the things I’ve been interested in a long time,” Parsons told The Birmingham News in 1987.

In particular, Parsons set out to challenge how his colleagues loaded the Education Trust Fund with pork projects.

His colleagues fussed, but Parsons filibustered the budget. He challenged the state Senate to ask the Alabama Supreme Court whether their non-education appropriations out of the ETF were legal. Lawmakers caved and asked for an opinion. And then they kept asking, in hopes of getting the answer they wanted.

Before the session was over, the state’s highest court gave them three. No matter how many times and in how many ways the Legislature asked the question, the court gave the same answer in so many words.

No, you can’t do that.

And then the legislature pretty much did what it wanted anyway.

Lawmakers stripped some of the more egregious pork projects out of the education budget, but they left in funding for non-education departments.

Parsons learned to use his law license as a superpower to wield against the Legislature. He sued. It wouldn’t be the last time. And he wasn’t the only one to sue, either.

Paul Hubbert, the head of the Alabama Education Association, followed behind him and took the state to court, too.

Legal precedent

The lower courts ruled that Parsons was right and the Legislature had broken the law.

Ultimately, the higher court heard Hubbert’s case first. It ruled in favor of Hubbert, saying ETF funding could be used for educational purposes only, as the law clearly said.

Mac’s lawsuit was rendered moot, but his point was validated — and Alabama’s state budget was thrown into chaos.

Perhaps more importantly, the court said the legislature could not un-earmark ETF money with a wave of its hand.

“[T]he removal or disregard of earmarking is not a matter properly to be included in an appropriation bill,” the court said.

In other words, once tax dollars make it into the ETF, they’re to be spent for education purposes only and no bill appropriating that money can undo that.

Which is the very thing Kay Ivey is currently trying to do today — directing education money to water parks and whatnot.

As a legal matter, this sort of thing was settled a long time ago — only so much time had passed that most folks had forgotten.

Everybody, it seems, but Mac’s old law partner.

I suppose there’s nothing stopping the governor or lawmakers from trying anyway, but they can’t do so with the assumption that they’ll have the Supreme Court on their side.

There’s a precedent — one that’ll be hard to overcome.

And at least one mischievous spirit still causing trouble from beyond the grave.

More columns by Kyle Whitmire

Is Kay Ivey’s education spending plan legal? No one from the state will say.

Alabama governor wants $100 million of school funds for prison construction