Alabama planned to release hundreds of prisoners early. What went wrong?

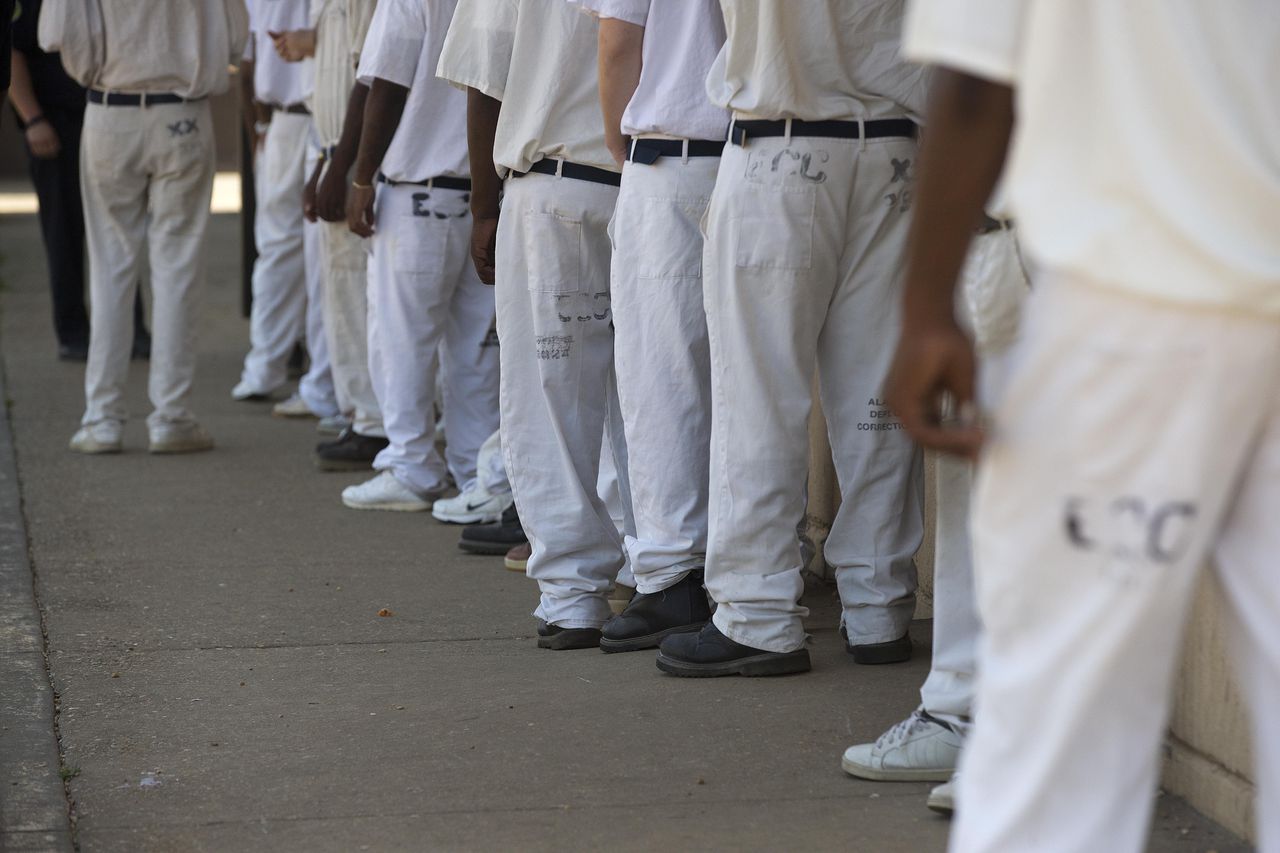

On Tuesday, about 400 people were set to walk out of Alabama prisons and work release centers, some just days or weeks ahead of the end of their sentences. A newly implemented law made their release possible, and the prisons were going to outfit each of them with ankle monitors to ensure they didn’t get into trouble when they walked out of the prison doors.

The plan was clear: Prisoners get out a little early, but this way they could be made to wear an ankle monitor.

But some police clamored that dangerous people were being set free, and the Alabama Attorney General sued the state’s corrections and paroles departments, arguing over the way the plan was handled.

But the plan was approved by Republican lawmakers just two years earlier. So why was there so much concern? And why didn’t it work as designed?

“Everyone is taking advantage of this thing, acting like nobody knew,” said longtime Alabama corrections officer Stacy George. “This is the best thing Alabama has ever done in the history of prison reform. It’s the best thing for the citizens I’ve ever witnessed.”

About 300 people were released this week. That number would have been higher, but there were issues, raised by the attorney general, about not notifying victims or victim’s family members of the impending release. The planned mass release didn’t happen, and instead dozens were released each day throughout the week. The last inmate release as part of the initial rollout of the law is now set to happen Tuesday, Feb. 7.

The state had more than a year to make the notifications.

Many in Alabama were pointing fingers at the prison officials for bungling the release. An Alabama Department of Corrections spokesperson didn’t respond when asked why the letters weren’t sent or calls weren’t made to victims or victims’ family members during that time, or what the department spent that time doing. The law is also not clear if the ADOC was the only agency who was supposed to make those notifications.

What does the law say?

State Rep. Jim Hill is a former circuit judge in St. Clair County. He introduced the law to provide a period of time for inmates to be released early from prison and required to comply with electronic monitoring.

Many of the 369 set to be released in the initial rollout, named on a list obtained by AL.com, were being released just a few weeks early. Only a few were not set to end their sentence this year. The average time shaved off was 167 days, and each could be required to wear an ankle monitor for that period.

“I think that it’s a matter of keeping the public as safe as we can,” said Hill on Wednesday, “and having people that we have released from prison in a situation where they are supervised for at least some period of time prior to the time when they aren’t supervised at all.”

The formula in the law for how long a person released early should be supervised is as follows:

- For those with sentences of 5 years or less, three to five months.

- For those with sentences of more than 5 but less than 10 years, six to nine months.

- For those with sentences of more than 10 years, 12 to 24 months.

No one can be monitored beyond when their sentence ends—when they would have gotten out of prison anyway.

Sex offenders whose victim was a child are not eligible for the early release.

The law, updated and approved in 2021, was designed to take effect Jan. 31, 2023. Inmates whose victims had been notified were released Tuesday, along with those convicted of victimless crimes.

A statement from the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles said parole officers “will continue electronic monitoring until the proper assessments are conducted and further instruction is received.”

What went wrong

Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall filed a lawsuit Monday, the day before the law went into effect, arguing against early release because most inmates’ victims or victim’s families were not notified.

ADOC Commissioner John Hamm said in a letter presented in court that he didn’t think it was necessary to postpone the initial release, but that the prison system would not release anyone if the victim was not notified properly.

Most legislators believe the ADOC was responsible for that victim notification. Lawmakers say an early version of the bill seemed to suggest ADOC was supposed to make the notifications. But the final law doesn’t make that clear.

Hamm’s letter to Marshall said ADOC will handle the notifications.

The last of the initial release is set to happen next week, but the pardons board said more eligible inmates will be released in the coming months.

Cullman County Sheriff Matt Gentry and Cullman County District Attorney Champ Crocker held a press conference Thursday, saying they learned of the early release just days ahead of time and that inmates need to serve their entire sentence behind bars in order for justice to be served for victims.

Other law enforcement officials and district attorneys across the state echoed the concerns.

Blount County District Attorney Pamela Casey said Thursday night that one of the released inmates from her county—who spent decades in prison for murder—was released without an ankle monitor. She spoke with Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles Director Cam Ward, who was able to ensure the man received a monitor by Friday morning.

“What saddens me most about the whole situation is had I not asked, had I not looked out, trying to figure out what was going on or check on him, he wouldn’t have (gotten a monitor),” Casey said in a video posted to Facebook.

“And I really don’t feel like we should have to be following up on every one of these inmates, because I have enough work to do as it is without trying to confirm that everybody else is doing their work.”

In a statement Friday, a spokesperson for the pardons and paroles bureau said, “all people released to mandatory supervision are equipped with electronic monitoring.” Ward said the bureau is “doing everything we can to ensure public safety.”

“Public safety is the highest priority for the Bureau.”

Alabama state Rep. Chris England took to social media to vent about the rollout, tweeting that the ADOC didn’t finish the job. “The bill was signed October 1, 2021. 16 months ago. What exactly has (ADOC) been doing for the last 16 months? It certainly hasn’t been properly managing our prison system,” he posted.

“Are we supposed to believe that the same people that couldn’t make it happen in 16 months will now get it done before those scheduled to be released get to the end of their sentence?”

He continued, “Regardless of how anyone feels about the law, our government agencies must follow it. Especially here. There is too much at stake. Victims deserve it. Those individuals being released deserve it. We, as a community, deserve it. (Ivey) should demand it.”

Ivey’s communications director Gina Maiola said that the governor will always advocate for victims, and that this policy is “common sense.”

“Under Governor Ivey, public safety will always be at the forefront, and she will always be an advocate for victims and an upholder of justice,” said Maiola. “This is a pro-public safety, pro-common sense measure and implemented while respecting the rights of crime victims.”

$10 and a bus ticket

George, a longtime corrections officer for the ADOC who has also worked as a county commissioner and has run for governor, said he has never had so many messages from friends and colleagues about a policy. He said his phone has been flooded with questions asking his opinion on the release and if the public should be concerned about former inmates coming back to their communities.

Early release with supervision should be welcomed, George said. He doesn’t understand the outrage. The policy gives the state oversight on people who otherwise would walk free without supervision—something he said should never happen.

“They shouldn’t be against this, this is a very positive thing,” he said Thursday. “We have to get these people out in the community somehow and have people look at them in a different way.”

If a person serving time behind bars or at a work release center is granted parole—something the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles isn’t doing often, according to their own data—they are subject to electronic monitoring, frequent visits with a parole officer, drug testing, and other factors. If the same person serves their entire sentence in an ADOC facility, they are free to go at the end of their sentence. Meaning, they do not have to check in with a parole officer, undergo drug testing, wear an ankle monitor or any other restrictions.

Alabama used to be a model for other states when it came to parole. Between 2015 to 2018 the number of inmates granted parole rose steadily, getting people out of what the Department of Justice has called dangerous and overcrowded Alabama prisons.

That changed after 2018. Data from the pardons board shows that each year since, the rates of inmates who were granted parole declined steeply, ending 2022 with a just 10% approval rate.

Now, many inmates are serving their entire sentence behind bars and walking completely free upon release. George said that’s a problem. “If someone gets out, I would rather they get out six months early and have an ankle monitor on to see” what they are doing, he said.

George used several examples: If a convicted stalker is released, people should want to monitor to see if he or she is following their victim. If a drug dealer is released, people should want to know if they are back at a well-known place for opioids.

George leans on his personal experience to frame his perspective. “I have been that guy who dropped off an inmate at the bus station with $10 and a bus ticket to the same place that sentenced them.”

“I do not think people should panic over this issue. It just needs to be explained in a little different way.”

See more: