The debate around NIL and Alabama high school athletics is here

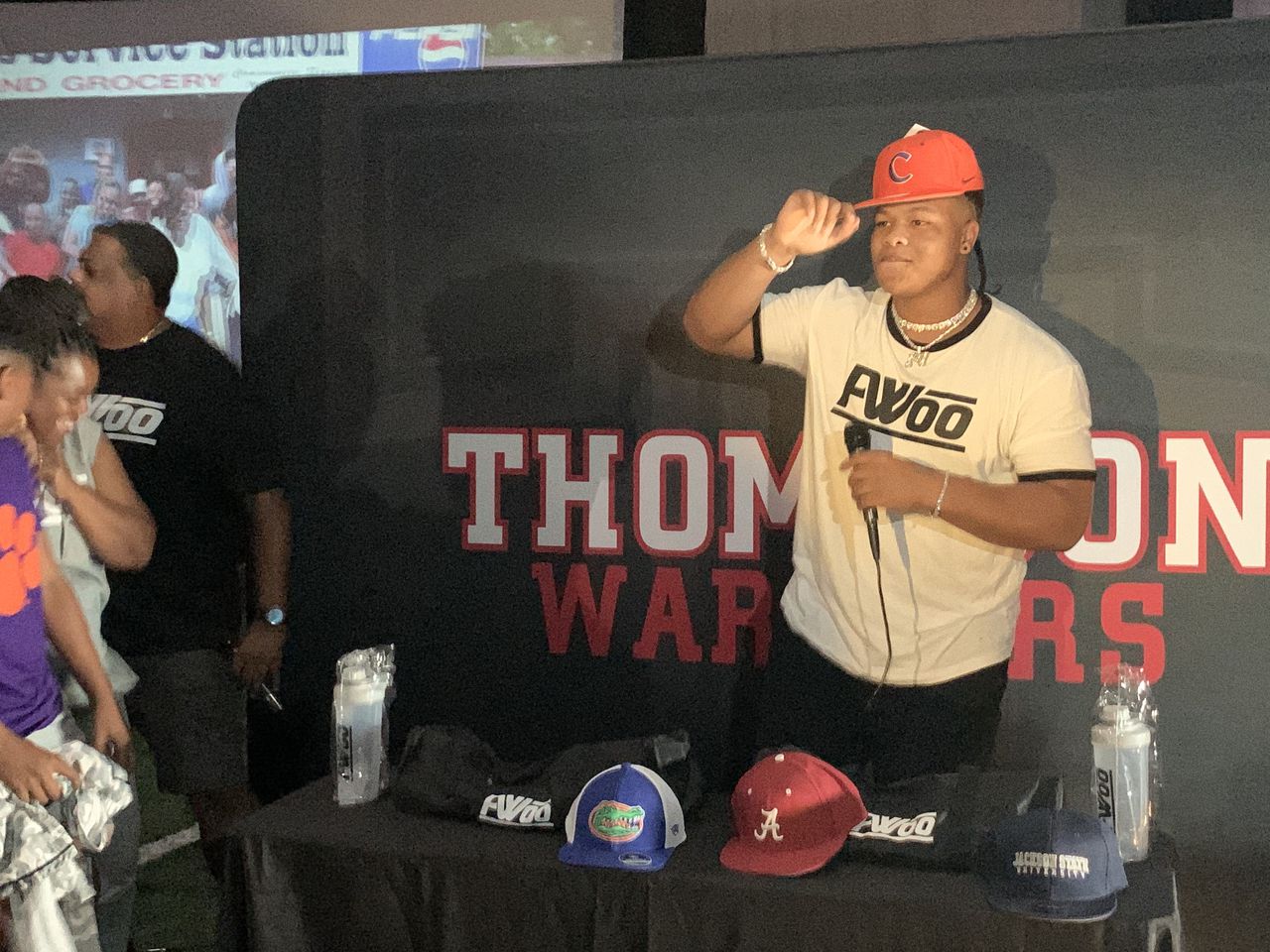

Peter Woods walked into Thompson High’s turf-laden field house last July as one of the best senior defenders in the country. He was on the path to four-straight Alabama state titles with a five-star ranking, and he invited friends and media to see him reveal his college future.

Some recruits look at the event as a party or a necessary end to a tiring process. For Woods, the pomp had to match the occasion. Sweets were rolled in on dollies. Florida-based football YouTuber Coach Haynes hosted a live stream. After a video played in which Woods chose Clemson, cameras swarmed Woods at the center of the room.

He posed in front of a school backdrop, lights flashing off a diamond necklace and strategically placed merchandise: Water bottles, duffle bags and a crisp, white t-shirt on Woods’ 6-foot-3, 270-pound frame all featured the ‘PWoo’ logo.

Woods and his parents, Jermaine and Devon, decided his night would be not just a celebration, but a brand “launch.” What they didn’t know at the time though, was the event pushed the boundary of Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) in Alabama high school sports.

The Alabama High School Athletic Association (AHSAA) abides by the amateur policy. As director Alvin Briggs summarized in 2021, student-athletes “can’t use (their) athletic abilities to gain anything financially.” Still, under the current guidelines, players retain their eligibility as long as they don’t individually receive anything in return.

Woods didn’t sell any gear while attending Thomspon. But for his commitment event, knowing eyes would be on him, he made sure signage was visible months before his profit window opened. Basically, elite prospects and their families are crafting NIL strategies whether the AHSAA gets involved or not.

Peter Woods at his commitment ceremony on July 8, 2022, at Thompson High in Alabaster, Ala.

More than 25 state legislatures have moved toward some form of NIL for non-collegiate athletes, per an Opendorse database. This summer, Louisiana became the first southern association to change its mind. Tennessee started allowing deals in mid-December. Last week, Georgia announced its plan to eventually allow high schoolers to cash in.

Multiple varsity coaches confirmed to AL.com that out-of-state coaches in NIL-legal territories are recruiting players. Some worry the state will fall behind and lose talent without a policy change. Others, like Nick Saban at a Montgomery hotel in front of hundreds of Alabama coaches on Jan. 26, worry NIL would fundamentally change recruitment in high schools as it has at the collegiate level.

An AHSAA representative declined to answer if there’s been any reexamination of the current protocol or if they have investigated any eligibility cases sparked by players receiving compensation. In the meantime, the national debate will continue while the next generation is taking varied approaches to building their ‘brand,’ a catch-all term combining their skills, personality and online presence.

“Coach (Nick) Saban will get it changed I bet,” Clay-Chalkville head coach Drew Gilmer said last summer. “That’s what going to have to happen. Why would a kid stay here for another year of high school when he can go to Louisiana and maybe make $100,000? I’d pack up and move too.”

The Alabama legislature was one of eight that changed its NIL laws in the college ranks in 2022 to be less restrictive than originally passed following NCAA v. Alston. Employees at Auburn, for example, can now help connect businesses with students. What happens when the same model comes to Friday nights?

Experts have previously cited a NIL education gap for students seeking info. The National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHSHS), which counts Alabama as a member, has let individual organizations set their own rules. At national scouting events, some Alabama players have heard the Yellowhammer state is predicted to be among the last holdouts. Though from lawmakers to Karissa Niehoff, CEO of the NFHSHS, the sentiment is common: There’s an “increasing need” for guidance.

Gardendale’s Kelby Collins celebrates after sacking Parker’s Tyson Allen in Birmingham, Ala., Saturday, Sept. 17, 2022. (Mark Almond | [email protected])

Alabama enrollee and Hewitt-Trussville defensive lineman Hunter Osborne is on social media “pretty heavily,” he said. He knows part of the game is interacting with fans. Osborne asks himself three questions before posting: How will it benefit me?; How will it be viewed?; How will the fans love it?

“There’s an element of marketing and self-branding that’s obviously important to these recruits. It’s smart business. It’s good business to do so early to kind of start dealing with the things you’re going to deal with any way in this era,” Sports Illustrated director of recruiting John Garcia Jr. said.

Kelby Collins, a Florida Gator and Gardendale edge rusher, made an internal calculus. Advertisers want a large platform. Players want followers. Ergo, more followers equate to more NIL money. A kid of few words, as his mother Donchelle Collins describes him, Kelby looked to his younger brother, Drew Collins, a junior at Gardendale with no formal digital media training, to run a TikTok and YouTube channel on his behalf.

Both Osborne and Collins have their own wordmarks and have seen a boost to their NIL value on sites like On3, which tries to quantify how much players are worth in ad deals. Collins admitted at times social media pressures took away “from the fun” of his senior year. His teammate, future Arkansas cornerback Dallas Young, said players aren’t mature enough for NIL consequences.

“I don’t know how I feel overall,” Parker running back and Tennessee signee Khalifa Keith said. “You can’t take money out of a kid’s hand ‘cause you can’t figure out what we’re going through.”

The other side of the argument is just as passionate. The flow of transfers is already weakening the bonds of communities, coaches reason. Infusing money would exacerbate issues. Players used to grow up together and contend for state titles together. With NIL, one coach forewarned running backs fighting in locker rooms for carries. (Though in a recent survey of 1,000 student-athletes, just 8% said they witnessed locker room strife caused by NIL deals.)

When asked what they thought of Alabama potentially bringing NIL to high school, coaches said it would be an “armageddon” and a “travesty,” predicting the state “would fight it tooth and nail.” That’s without considering the financial inequalities riddled within the AHSAA’s 500-plus member schools.

While some, like Vestavia Hills’ Robert Evans, said he already knows of businesses that’ll jump at a chance to give their local school a monetary edge, other coaches, like Parker’s Frank Warren, realize that some programs already struggle to fund equipment and travel costs and they would never be able to compete with four-figure sponsorship deals.

“If it comes to Alabama it’s going to be hard. This state is large and there are a lot of rural schools with great athletes. I’m from Georgia, I live outside of Macon (Ga.), and for a kid to get an opportunity to leave a rural school and go to an Atlanta school, they’ll jump at the bit for that. Imagine kids down in Wilcox (County) or in the Black Belt getting an opportunity to leave your high school and go to a bigger program? Eventually, it’s going to crush some of these rural schools,” Loachapoka offensive coordinator Travis Carswell said.

85

Best of AHSAA Super 7 Football Championships

Twenty-nine-year head coach Jerry Hood summarized the sentiment among longtime gatekeepers of the game as well as any: NIL would “erode an eroding sport.” Yet, the Alabama Football Coaches Association convention in which Saban spoke out also featured a talk by Keith Eccker, the head of Eccker Sports, leading an info session on the topic for high school coaches. It was the next step of a partnership between the company and the ALFCA, which partnered together in 2022.

Regardless of moral arguments or hesitancy from state officials, Jermaine Woods and other parents are considering their current situation. Booster-funded collectives are contacting prospects and offering pay-for-play scenarios against NCAA rules. Nearly all Division-I players have some type of social media following which is boosted by appearances on national television. Waiting for college enrollment to start the NIL process would be “reactive” and that’s not how the Woods’ raised their children to approach life.

Devon Woods designed the ‘PWoo’ logo, after her son’s nickname on the team, in 2020. She had over 10 years of experience in hotel marketing and noticed the attention other parents gave them when they wore branded shirts on Friday nights. She researched what was and wasn’t permitted by the AHSAA. They started ordering swag for friends to wear. During July’s commitment, Peter Woods advertised a merchandise table in the back of the room. They later said they gave away items, only accepting money as “gifts,” none of which went to Peter.

As Woods and other teenagers graduate into opportunities worth millions of dollars — and the AHSAA stays quiet — some Alabama families have been linked by foresight and have acted, in their opinions, accordingly.

“You don’t wait until it goes on the shelf to begin letting people know,” Jermaine Woods said. “… it was an introduction. It was not in any way, meant to affect NIL in Alabama.

“If (Peter’s) technique and opportunities in football are being taken care of, then it would be our responsibility to also guide him in making sure any opportunity that happens in NIL is also pre-taught. … NIL became a reality, we wanted to make sure that we prepared.”

Nick Alvarez is a reporter for Alabama Media Group. Follow him on Twitter @nick_a_alvarez or email him at [email protected].